GRSG 2024 Reading Notes

The GRSG 2024 Reading Notes

Introduction

The Gravity’s Rainbow Support Group (GRSG) began in June 2020 as a “reading group” of two people. It was a support mechanism to plow though Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (a book you should never try to read alone) during the pandemic. The GRSG took some of the difficulty out of reading this challenging book and provided a way to keep two now-retired college chums (from Indiana University) Francis Walker of Winston-Salem, North Carolina and Murray Browne of Decatur, Georgia in touch. Basically, we decided to keep this good thing going.

This page is the fifth installment of our reading-discussion notes of books we assigned ourselves in 2024. Our reading notes include favorite quotes and passages and some of our discussion about the book. Don’t expect coherent prose or well thought out arguments, but our musings may provide insights to your own understanding and enjoyment of these books.

Here are the lists of books read and discussed in previous years:

2020 Reading Notes Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon; The Denial of Death by Ernest Becker; Pnin by Vladimir Nabokov

2021 Reading Notes The Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War by Drew Gilpin Faust; Absalom, Absalom by William Faulkner; Stilwell and the American Experience in China, 1911-1945 by Barbara W. Tuchman; Cultural Amnesia by Clive James; The Periodic Table by Primo Levi; The Historian’s Craft by Marc Bloch; An Inventory of Losses by Judith Schalansky; Homeric Moments: Clues to Delight The Odyssey and Illiad by Eva Brann; Homage to Catalonia by George Orwell

2022 Reading Notes The Age of Anger: A History of the Present by Pankaj Mishra; Mountains and a Shore: A Journey Through Southern Turkey by Michael Pereira; The Life and Opinions of Tristam Shandy Gentleman by Laurence Sterne; Grant by Ron Chernow; The Innocents Abroad by Mark Twain; The U.S.A. Trilogy by John Dos Passos (The 42nd Parallel, 1919, and The Big Money); Under the Net by Muriel Spark; Two Wheels Good: The History and the Mystery of the Bicycle by Jody Rosen; Red and Black: A Chronicle of 1830 by Stendhal.

2023 Reading Notes A Path Lit by Lightning: The Life Lit By Lightning by Robert Maraniss; Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad; Algorithms to Live By: The Computer Science of Human Decisions by Brian Christian and Tom Griffiths; Force: What It Means to Push and Pull Slip and Grip Start and Stop by Henry Petroski; On Bullshit (2005) by Henry G. Frankfurt; Dubliners by James Joyce; TransAtlantic by Colum McCann; Regeneration by Pat Barker; Under the Eye of Power: How Fear of Secret Societies Shapes American Democracy by Colin Dickey; The First World War by John Keegan; Frankenstein by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley; Galileo and the Science Deniers by Mario Livio

And now we move on to 2024:

Down and Out in Paris and London (1933) by George Orwell

We began the new year, revisiting an author we thoroughly appreciated in 2021 — George Orwell. In Homage to Catalonia (1938), an account of the Spanish Civil War was a mixture of battlefield/urban fighting and commentary on the political chaos, which led ultimately to the rise the decades of harsh rule under Franco.

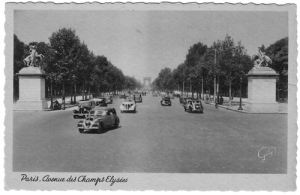

In Down and Out, Orwell takes us first to the front lines of the Paris restaurant business during the early part of the Depression where he lived hand to mouth in filthy and infested single occupancy hotel rooms. Accompanied by his Russian friend Boris a former military man before the Bolshevik Revolution, he eventually found work as a plongeur. ( Translated from the French it means “diver” or “pearl diver” which is slang for dishwasher) Orwell is a master of description in his accounts of the conditions, the people, the hierarchy of restaurant personnel. He includes numerous sidebar stories about his fellow down and outers. Orwell is not a writer that evokes pity or outrage, rather he is matter-of-fact in the world he describes in detail (but he is never verbose or judgmental).

In the second half of this short book, the narrator arrives London expecting work from a friend as a caretaker, only to find out that his employment is delayed for a month. With few resources left over from his stint in Paris, Orwell joins the bands of homeless men who roam from church to shelter seeking a place to sleep and food (mostly bad tea and toast). Accompanied by men such as Paddy and Bozo (a screever – one who paints on sidewalks), Orwell goes from city to city as transients are not allowed to stay in a place for more than a night. Orwell gives us the smells of urine, filthy sheets and unwashed men. The book ends with Orwell’s assessment of the situation and suggestions on how to improve the conditions for these men (and they are mostly men).

Poverty & Homelessness

One of the strengths of the books is a look at the mindset of the homeless. It raises many thoughts and questions:

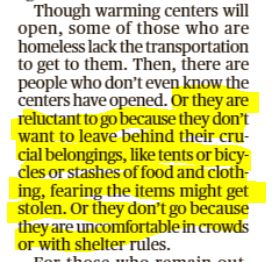

How has tent living changed the nature of homelessness? (In Orwell’s England, the homeless had to change shelters every night—heading off from one to another–often miles apart). This is in contrast to Atlanta, where the overpasses and train areas are populated with tents from the homeless. In recent years, an interstate overpass and bridge overpass have caught fire. A recent article about the homeless in the Sunday edition (1/14/24) Atlanta Journal-Constitution, how fires are maintained or not maintained makes one wonder this doesn’t happen more often. Just as in Orwell’s day, many homeless refused the restrictions of shelters and refused them for fear of leaving their possessions on the outside.

How has tent living changed the nature of homelessness? (In Orwell’s England, the homeless had to change shelters every night—heading off from one to another–often miles apart). This is in contrast to Atlanta, where the overpasses and train areas are populated with tents from the homeless. In recent years, an interstate overpass and bridge overpass have caught fire. A recent article about the homeless in the Sunday edition (1/14/24) Atlanta Journal-Constitution, how fires are maintained or not maintained makes one wonder this doesn’t happen more often. Just as in Orwell’s day, many homeless refused the restrictions of shelters and refused them for fear of leaving their possessions on the outside.

There is very little mention of mental illness in the book making one wonder was it less of a factor or was Orwell just not picking up on it? Clearly, drug use was limited in this population, presumably due to cost—even alcohol was beyond the means of many. Orwell does mention one incident : ” Paddy and I had scarcely a wink of sleep, for there was a man near us who had some nervous trouble, shell-shock perhaps, which made him cry out ‘Pip!’ at irregular intervals. It was a loud, startling noise, something like the toot of a small motor-horn.”

Quotable Orwell

“The Paris slums are a gathering-place for eccentric people — people who have fallen into solitary, half-mad grooves of life and given up trying to be normal or decent. Poverty frees them from normal standards of behavior, just as money frees people from work. Some of the lodgers in our hotel lived lives that were curious beyond words.” Chap 1

“You thought it (poverty) would be terrible, it is merely squalid and boring.” Chap 3

The great redeeming feature of poverty; the fact that it annihilates the future.” Chap 3

“And there is another feeling that is a great consolation in poverty. I believe everyone who has been hard up has experienced it. It is a feeling of relief, almost of pleasure, at knowing yourself at last genuinely down and out. You have talked so often of going to the dogs–and well, here are the dogs, and you have reached them, and you can stand it. It takes off a lot of anxiety.” Chap 3

“Hunger reduces one to an utterly spineless, brainless condition, more like the after-effects of influenza than anything else. It is as though all one’s blood had been pumped out and lukewarm water substituted.” Chap 7

“A man receiving charity practically always hates his benefactor”

https://bookshop.org/widgets.js

Sidebar Stories

As mentioned earlier, Orwell breaks the narrative with sidebar stories about some of the people he spent time with in Paris and London. One memorable character was the Russian Boris, a former captain in the Second Siberian Rifles who accompanied Orwell to look for work in restaurants and hotels. Boris was philosophical, but seeing things in military terms. When was forced to abandon some of his belongings to escape paying his hotel bill, he says unflinchingly “Besides, one always loses something in retreat. Look at Napoleon and Berezina. He abandoned his whole army!” And when their situation become even more dire and hopeless, Boris encourages Orwell by borrowing (WW I French general) Foch’s maxim. “Attack, Attack, Attack.”

In England Orwell travels from time with Paddy and Bozo. Orwell refers to Paddy as the first tramp that he knew well and spent a fortnight with him going from spike to spike (shelters). Paddy introduced the narrator to Bozo who was a screever – a pavement artist. We learn more about this world through Orwell’s interactions with these two seasoned tramps. Bozo tells stories of popular scams to be mindful of. Bozo’s observation “like most swindlers, he believed a great part of his own lies” reminds one of Donald Trump.

Profanity

The whole business of swearing, especially English swearing, is mysterious. Of its very nature swearing is as irrational as magic– indeed, it is a species of magic. Ch 32

Of course when you toss insults like this — profanity isn’t always necessary

“You call yourself a waiter, you young bastard. You’re not fit to scrub the floors in the brothel your mother came from.”

Questions on Classification

Was this book journalism or a fictional memoir? In other words. True story. or based on a true story?

John Southerland in his book Lives of the Novelists offers some insights. After returning from five years with the Imperial Indian Police in Burma, he returned to England (lived briefly with his aging parents) and “mediated his next step in life (which would appall them). He resolved to become a tramp. Why? It may have been self-punitive – his forty days in the desert.” Southerland doesn’t know whether Orwell was inspired by political views or literary homage to Jack London, W. H. Davies or Henry Miller. Anyway he spent two years slumming in the two cities.

This suggests to me Orwell could have walked away from this life style any time he wanted to. This makes a big difference. This indicates he was more of an embedded journalist than his own biographer. (Similar to Confederates in the Attic by Tony Horowitz?). That is not to detract from Orwell’s veracity, but it does explain the detached matter-of-fact tone of the book.

In his Amazon review of the book, Francis reinforces this opinion:

“Eric Blair (AKA George Orwell), in unadulterated detail, makes you feel as if you were there with him trudging, hungering and eking out an existence in the dives of Paris and London. While the author was better known for characterizing the dystopian world of “1984”, his own life provided him ample experience with interminable ennui, toil, malnutrition, filth, vermin and a society fit to dehumanize all but the most resilient of anyone lacking means. Not for the squeamish, the book delves into the psychology of impoverishment, the odd hierarchy of those it afflicts and barriers to addressing it; parts are still relevant to today’s homelessness crisis. Highly recommended for anyone interested in historical realism and immersive journalism. “

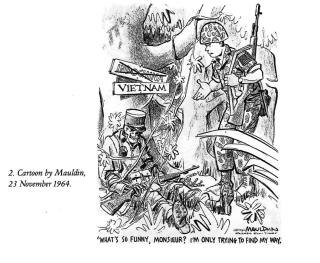

An Honorable Exit (2023) by Éric Vuillard

Our interest in France continues with Vuillard’s slim history on the country’s withdrawal from Indochina in 1954. However, history may be a stretch because compared to other historians we have read here at GRSG (Marc Bloch, Barbara Tuchman, Ron Chernow), our assessment of this book is that reads like almost like a movie screenplay that someone wants to pitch to a film production company. Vuillard writes from the perspective of the French officials including bankers who propped up the French government and the military even though many of them knew it was lost cause. These officials wanted an honorable exit and that was not going happen. Of course, as we know, the United States learned nothing from the French debacle.

Our interest in France continues with Vuillard’s slim history on the country’s withdrawal from Indochina in 1954. However, history may be a stretch because compared to other historians we have read here at GRSG (Marc Bloch, Barbara Tuchman, Ron Chernow), our assessment of this book is that reads like almost like a movie screenplay that someone wants to pitch to a film production company. Vuillard writes from the perspective of the French officials including bankers who propped up the French government and the military even though many of them knew it was lost cause. These officials wanted an honorable exit and that was not going happen. Of course, as we know, the United States learned nothing from the French debacle.

He gives accounts of different officials, but there is no footnote or mentioning of his sources—even the elegant couple on the cover of the book is not identified. This is a similar technique that Vuillard used in his book The Order of the Day about the Nazi Germany invasion of Austria in 1938. A review of Order in the The Guardian by Andrew Hussey captured Vuillard’s unusual style:

“This wry aside is characteristic of Vuillard’s dry and ironic style. Although the book has been described as nonfiction it is not straightforward (which is why it won the 2107 Goncourt, which is a prize for fiction). Instead it takes the form of a récit – a type of essay where the author is always present, zooming in and out on facts, details and marshalling arguments.”

For this reason, conventional historians who are suspicious of historical fictions have not been especially friendly towards this book.

There are several main threads that Vuillard focused on:

The Bankers

The French international bankers had already cut their financial strings from Indochina long before battles and Cao Bang (1949) and Dien Ben Phu (1954) and made enormous profits for their investors.

From Francis: Here is Vuillard going on a tear about those attending the Bank meeting: “Imagine actors who never revert to being themselves but go on playing their parts in perpetuity. The curtain falls, but the applause doesn’t snap them out of their role. Even when the auditorium is empty and the lights out, they never leave the boards. No use screaming at them that that’s enough, we get it, we know the story by heart: they’ll keep right on acting, treading and declaiming…. “

(Here, I just think Vuillard underestimates the necessary role of corporate double-speak, in this case, used here not to confuse the other members of the meeting, who knew well what was going on, but to minimize the potential for any fallout, should minutes of the meeting ever come to light. These are serious businessmen, not like so many of our half-baked politicians who get caught making hot mic comments.)

Relevant Quotes from others: A ‘sound’ banker, alas, is not one who sees danger and avoids it, but one who, when he is ruined, is ruined in a conventional and orthodox way along with his fellows, so that no one can really blame him. — John Maynard Keynes Essays in Persuasion 1933

To others we are not ourselves but a performer in their lives cast for a part we do not even know that we are playing. Elizabeth Bibesco Haven 1951 (posthumously)

Everybody has his own theater, in which he is manager, actor, prompter, playwright, scene-shifter, boxkeeper, doorkeeper, all in one, and audience into the bargain. — Julius Hare 1827

Dien Bien Phu

The Vietminh’s defeat of the French in the battle was described by Vuillard as the French garrison was “living, in the strictest sense, at the bottom of a chamber pot…and the Vietminh are occupying the entire rim of that chamber pot.” The Vietminh led by General Vo Nguyen Giap (who later was lead general against the Americans) made relatively quick work of the French army and its mercenaries. (Francis and I both remember Dien Bien Phu because of we were old enough to remember Khe Sanh the U.S. combat base that was under siege in 1968 and the worries that it would end up like Dien Bien Phu.

Vuillard is graphic in the conditions of the troops when they finally surrendered and the failed commander of that Indochina theatre General Henri Navarre, considering his remote oversight of the failure at Dien Ben Phu: “He was mortified. Dreading the weakness he felt, which actually might have made him more approachable, more human, he professed an ever greater firmness and became even more sectarian and retrograde. Page 114

This reminded Francis of a quote from Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach: We hold onto supports with redoubled strength when we feel them begin to sway

Allen Dulles and John Foster Dulles

“He (Patrice Lumumba, elected Prime Minister of the Belgian Congo) realized how badly he had underestimated the viciousness with they would preserve their power.” – p106

“If we granted rights to our colonized populations, we would be the colony of our colony”- Assembly President Edouard Herriot – p. 27

One of the unexpected sidebars is the chapter that are focused on Eisenhower’s Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and his brother CIA Director Allen Dulles. The former offered the French a couple of atomic bombs to remedy their situation. No surprise as the Dulleses sanctioned part of Lumumba’s torture and assassination in the Congo in 1961. The Dulleses also supported the overthrow of a duly elected pro agrarian government in Guatemala at the behest of the American United Fruit Company and removed the Prime Minister of Iran and replaced him with the Shah.

Why is the airport in Washington D.C. named after this guy?

https://bookshop.org/widgets.js

Poor Things (1992) by Alasdair Gray

Because Murray was asked to write an essay for the Tropics of Meta comparing Poor Things the novel, to the Oscar-nominated Poor Things the film, Francis joined in with the reading of the book. With his medical background he provided insights into the medical ethical aspects of both works. The essay, “Re-visiting Poor Things: The Book vs. the Movie is found here.

Because Murray was asked to write an essay for the Tropics of Meta comparing Poor Things the novel, to the Oscar-nominated Poor Things the film, Francis joined in with the reading of the book. With his medical background he provided insights into the medical ethical aspects of both works. The essay, “Re-visiting Poor Things: The Book vs. the Movie is found here.

We begin with Francis’ Amazon review because he draws a comparison to earlier English novels including Mary Bysshe Shelley’s Frankenstein which we read last year in the Gravity’s Rainbow Support Group (GRSG). Notes are here.

Poor Things is an inventive reconstruction of the Victorian novel. It modernizes it by discussing health matters and physicians, real and fictional, which captures the most advanced knowledge of the time; incorporating political and social issues without melodrama; and by discussing sexual relationships without being graphic or excessive. While it harbors elements of each of their styles, this book fills a void in the works of Trollope, Dickens, M. Shelley, Austen and Conan-Doyle. George Elliot wrote: “Imagination is a licensed trespasser: it has no fear of dogs, but may climb over walls and peep in at windows with impunity.” The reader is swept up in just such a caper in this story which proves diverting and delivers an insightful yet comic glimpse of the past.

One key observation about the book is that written in somewhat a Victorian-19th century style, but it does differ because it examines topics not usually found in these novels: Medicine, politics and sex.

Medicine

There is plenty of medicine in this book. The three main characters are physicians (Godwin and McCandless of course) if you include Bella who later  becomes a doctor later in the book’s epilogue.

becomes a doctor later in the book’s epilogue.

Gray captures some of the absurdity of medicine on page 222 when the doctors are “explaining” Bella’s condition.

“Charcot daringly suggests the amnesia has enlarged her intelligence by making her relearn things when old enough to think about them, which people who depend on childhood training hardly ever do.” They agree that she shows no signs of mania, hysteria, algolagnia, necrophilia, coprophilia, folie de grandeur, nostalgie de la boue, (nostalgia for mud) lycanthropy (transfer into a werewolf), fetishism, Narcissism, Onanism, irrational belligerence, unhealthy reticence and is not obsessively Sapphic.”

The culture of medicine even expands to the grave robbers who provide bodies to experimental surgeons such as Godwin. In the Historical Notes that follow the main novel (page 300) Gray writes about “The Resurrectionists This five-act play about the Burke and Hare murders is no better than the many other nineteenth-century melodramas based on the same very popular theme. Robert Knox, the surgeon who bought the corpses, is treated more sympathetically than usual, so the play may have influenced James Bridie’s The Anatomist.”

Page 306: “She (Bella) accepted Tolstoy’s view that human animals are prone to epidemics of insanity, like many thousands of Frenchmen going into Russia with Napoleon and dying there, when their country would have been no better off if they had conquered it. However, being a doctor she knew epidemics can be prevented if the causes are discovered.” (Well, not if Trump is in charge or the Florida Surgeon General!)

Politics

Although the Victorian novelists dealt with class issues the specifics of politics not much so. This is not true of the Gray novel. One of the characters Mr. Astley, who introduces Bella to his “bitter wisdom” in Chapter 16, provides his views and definitions of communists, socialists, anarchists mixed in with his railings about colonialism.

Sex

In the Victorian novels, sex is barely alluded too, not so much Poor Things. However compared to the graphic sex and nudity of the film version, sex is mentioned, but in broader terms. Or course, Gray is not above has included this woodcut illustrations of a nude Bella.

Wordplay and Humor

Gray writes with understated with plenty of wordplay. Bella’s creator Godwin is “God” for short, and their are many examples of wit in the dialogue— e.g. “you will find her more interesting that Flopsy and Mopsy put together” (the two rabbits that Godwin severed and reconnected in his early experiments).

Gray writes with understated with plenty of wordplay. Bella’s creator Godwin is “God” for short, and their are many examples of wit in the dialogue— e.g. “you will find her more interesting that Flopsy and Mopsy put together” (the two rabbits that Godwin severed and reconnected in his early experiments).

Then there is the Who’s Who parody of General Sir Aubrey la Pole Blessington career.

Of course, you wonder is General Blessington, a fictional character or did Gray pull this from some obscure Who’s Who entry and just add a few twists. Or is this an entirely creative exercise?

That is what is so demanding of the novel is that there are many extra notations, chapters and footnotes added to the main plot of Bella Baxter’s life. And one is not sure what is true and what is fabricated. Of course, Gray chimes his opinion in this quote:

“I also told Donnelly that I had written enough fiction to know history when I read it. He said he had written enough hi story to recognize fiction. To this there was only one reply—I had to become a historian.: Page xiii. This reminds one of the HL Mencken 1880-1956 quote : “Historian — An unsuccessful novelist.”

Final Thoughts

This book was a challenging, but worthy read.

https://bookshop.org/widgets.js

I Never Did Like Politics: How Fiorello La Guardia Became America’s Mayor and Why He Still Matters (2024) by Terry Golway

The long title tells it all. Francis definitely liked the biography more than Murray, but after our discussion Francis was very convincing that at the book deserves our GRSG approval. But let’s begin with Francis’ review which he posted on Amazon.

When it comes to airport names, some are bestowed belatedly (i.e. Dulles, JFK) and others are earned. Fiorella LaGuardia, who never did like politics, earned his, after simultaneously serving in WW! as a pilot and in the US government as a congressional representative, and later after fighting for its construction as mayor of New York. The book recounts this and many other episodes in the life of this amazing individual who looked after his constituents and served his country in admirable fashion. More to the point, it describes a world where democrats (e.g. FDR and Harry Truman) and republicans (Fiorella La Guardia) worked together to solve local, national and international problems. Those despairing of today’s political gridlock will find this book refreshing in that it shows how American statesmen of a prior generation cut through red tape and party solidarity to forge the alliances and compromises that led our country out of the Great Depression and two world wars. Highly recommended.

https://bookshop.org/widgets.js

However, we both agreed that Golway’s narrative style was confusing as he skipped around timeframes quite a bit. La Guardia had a plenty of different life experiences besides being a congressman, a mayor, a military man and his final position as the head of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA). Although La Guardia was a longtime Republican, he was appointed to the position by the Democratic President Harry Truman because of La Guardia’s reputation and a doer and a no-nonsense administrator.

We also agreed that despite his naysaying of his own position in politics, La Guardia was a demagogue, but “do-good demagogue” (kind of like a benevolent monarchy because that pair of words are not often put together).

Quotable

To Galway’s credit, his writing ability was solid and appreciated. Below are some favorite passages:

Page 26: When his fellow Republicans urged La Guardia to dial it down a notch, he replied that he was simply pointing out that his opponent (Michael Farley) would not be a good congressman. In fact, La Guardia added, he wasn’t even a good bartender. He did not offer any evidence to support this assertion. But he seemed pretty certain of it.

Page 32: During a bombing raid on an Austrian airfield, Negrotto made a sharp turn at about 110 miles an hour just as La Guardia let the bomb loose. “How’d I do,” the American shouted over the plane’s engine noise. “It was the best speech you ever made,” came Negrotto’s reply.

Page 40: His speech marked the beginning of the role he would play over the next decade as one of the country’s most vocal critics of Hitlerism and fascism, and one of its most enthusiastic defenders of democracy at a time when it was in mortal peril.

Page 47: The mayor told White: “It occurred to me that the committee had better divide. You could continue as chairman of the ‘Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies with Words’ and the rest of us would join a ‘Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies with Deeds.’”

Page 48: Advised that Hitler’s government had demanded extra police protection for German diplomats in New York, La Guardia made sure that the extra cops assigned to the Nazis were Jewish.

Page 61: And such a voice it was: FDR’s resonant baritone and patrician accent were a perfect fit for radio, just as, years later, John F. Kennedy’s youthful good looks and cool demeanor were made for the newborn television age.****

Page 73: Politics may be the only profession in America whose practitioners—sometimes the best of them, often the worst—feel obliged to insist that they are not what they so clearly are****

Page 79: Not without reason, Oliver Wendell Holmes supposedly said that FDR was blessed with a first-class temperament. Fiorello La Guardia, by contrast, had a first-class temper. He was forever raging against the machine, finding nothing of value in political leaders like Sullivan and his successors, several of whom by chance were named … Sullivan.

Page 141: TR’s famously witty daughter, Alice Roosevelt Longworth, said that her father wanted to be the corpse at every funeral, the bride at every wedding, and the baby at every christening.

Page 145: The commanding general insisted that the impetuous captain had violated army regulations. Well then, La Guardia said, perhaps he could arrange to have the army’s regulation changed. “I thought the man would bust with rage,” La Guardia wrote of the general whose name he could not remember years later. “He pounded the desk violently [and] called me insolent [and] impertinent.” A colonel standing nearby mentioned that the impertinent captain also happened to be a member of Congress, and perhaps he could indeed get army regulations changed. The conversation, La Guardia recalled, suddenly took on an entirely different tenor.

Page 185: Historian Joel Schwartz said that NYCHA was looking for “the heroic poor”—in other words, as Kessner writes, “those who overcame trying circumstances to raise decent families and nourish middle-class aspirations.”

Page 147: The aldermen over whom La Guardia presided no doubt were a step or two above their more rapacious predecessors in decades past, the worst of whom were known unaffectionately as the “forty thieves.” Still, few would ever confuse the board of aldermen with the Mormon Tabernacle Choir.***

Page 200: La Guardia Field became the busiest airport in the world within a year of its opening, a development that came as little surprise to the facility’s namesake.

La Guardia Notables

Although he his most well known as the mayor New York and the airport named after him, there are other lesser known aspects of La Guardia.

La Guardia read the comics several times during a newspaper strike in July, 1945. Those looking for an explanation for the Little Flower’s success should visit WNYC’s online archives and listen to him read Little Orphan Annie or Dick Tracy. It explains everything. https://www.wnyc.org/story/44460-poor-little-annie/

La Guardia read the comics several times during a newspaper strike in July, 1945. Those looking for an explanation for the Little Flower’s success should visit WNYC’s online archives and listen to him read Little Orphan Annie or Dick Tracy. It explains everything. https://www.wnyc.org/story/44460-poor-little-annie/

After serving as mayor, President Harry Truman (not always a political ally) appointed La Guardia as the head of the UNRRA to oversee the distribution of food and aid to refugees after World War II. It made sense because La Guardia had a long history not tolerating bureaucracy and graft–no matter whose feathers were ruffled.

In 1924 as a congressman, La Guardia worked with Senator Frank Norris of Nebraska to keep industrialist Henry Ford from taking over the building of dams on the Tennessee River. La Guardia felt that these should be Federal owned public works instead of private entities. One of the early dams was the Wilson Dam that was completed in 1925. It is located between Muscle Shoals and Florence Alabama and is still operational.

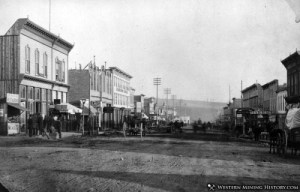

Angle of Repose (1971) by Wallace Stegner

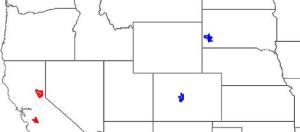

This book had been recommended to Murray by a respected reading friend years ago and when he picked it up at the Decatur Friends of the Library sale for free (with my volunteer dollars), it struck him like a book that may be a good GRSG candidate. The main character of Stegner’s novel, which was awarded the Pulitzer in 1972, is Lyman Ward an aging historian, who is digging deep into his own family history via his grandmother Susan Ward who was an illustrator raised as an East Coast woman of culture who hung with literary types. After marriage, Susan followed her engineer husband Oliver Ward’s “through the American West as he developed mining operations in New Almaden (south of San Jose), Deadwood (South Dakota), Leadville, Colorado (near Denver), Mexico and Boise, Idaho. A great source of photographs and maps of mining to is found at westernmininghistory.com

Stegner impresses both Francis and me in effortless transition (not easy to do) switching from the narrator Lyman and the stories of his grandmother. Lyman has lost a leg due to bone disease and lives by himself near Nevada City, California with assistance from his son Rodman and a caretaker woman and her family who lives nearby. “History is his habit and his wedded wife,” says Lyman. (One thing that struck us odd about Lyman is that initially we think he is older than he really is. He is only 58 years old! A pup, but poor health can age one prematurely.)

History and the Future

If Henry Adams, whom you knew slightly, could make a theory of history by applying the second law of thermodynamics to human affairs, I ought to be entitled to base one on the angle of repose, and may yet. There is another physical law that eases me, too: The Doppler Effect. The sound of anything coming at you–a train, say, or the future–has a higher pitch than the sound of the same thing going away. If you have perfect pitch and a head for mathematics you can compute the speed of the object by the interval between its arriving and departing sounds. I have neither perfect pitch nor a head for mathematics, and anyway who wants to compute the speed of history? Like all falling bodies, it constantly accelerates. But I would like to hear your life as you heard it, coming at you, instead of hearing it as I do, a sober sound of expectations reduced, desires blunted, hopes deferred or abandoned, chances lost, defeats accepted, griefs borne. I don’t find your life uninteresting, as Rodman (the grandson) does. I would like to hear it as it sounded while it was passing. Having no future of my own, why shouldn’t I look forward to yours?

Passages such as this reminded Francis of similar quotes:

“It is perfectly true, as philosophers say, that life must be understood backwards. But they forget the other proposition, that life must be lived forwards.”–Soren Kierkegaard

Oh, and there is Ambrose Bierce:

Future. future, n. That period of time in which our affairs prosper, our friends are true and our happiness is assured. – The Devil’s Dictionary.

Hope: Desire and expectation rolled into one.

Delicious Hope! when naught to man it left —

Of fortune destitute, of friends bereft;

When even his dog deserts him, and his goat

With tranquil disaffection chews his coat

While yet it hangs upon his back; then thou,

The star far-flaming on thine angel brow,

Descendest, radiant, from the skies to hint

The promise of a clerkship in the Mint.

– Fogarty Weffing (Ambrose Bierce)

– Ambrose Bierce: The Devil’s Dictionary.

Writing Style and Influence on Other Writers

From the Introduction of the book by Jackson Benson page xxix (written in 2000), he cites Joseph Conrad who he thinks influenced Wallace Stegner:

Here is Joseph Conrad: “My task, which I am trying to achieve is, by the power of the written word to make you hear, to make you feel—it is, before all, to make you see. That—and no more, and that is everything.” (We read Heart of Darkness last year.)

( Francis: This resonates with something else I read: “Art does not reproduce what we see; rather, it makes us see.” Paul Klee, he may have based this on Conrad, who was older than Klee by about 20 years).

Stegner also taught at University of Wisconsin, Harvard University, but is most known as a professor who started the creative writing program at Stanford. His students included Larry McMurtry, Thomas McGuane, Edward Abbey and Wendell Berry and Sandra Day O’ Connor (but what did she ever write?)

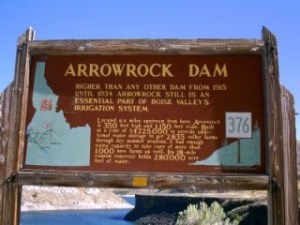

The book is a showcase for Stegner as a writer of the West and environmentalism though I would hesitate to pigeonhole him as such (Lyman Ward remarks that he “is not writing a book on Western History.” ) However, one cannot help think when Stegner/Ward mentions John Wesley Powell (a huge figure in water rights in the West and the namesake of Lake Powell) or Oliver Ward (Lyman’s grandfather) efforts to build canal near Boise, Idaho and to irrigate scrub lands into arable land. (not necessarily a good idea — See the Marc Reisner’s 1993 book Cadillac Desert) . Interesting enough Arrowrock Dam was completed in 1914 and it was tallest dam of its time when completed and the sign boasts how important the dam is to the Idaho irrigation systems.

The book is a showcase for Stegner as a writer of the West and environmentalism though I would hesitate to pigeonhole him as such (Lyman Ward remarks that he “is not writing a book on Western History.” ) However, one cannot help think when Stegner/Ward mentions John Wesley Powell (a huge figure in water rights in the West and the namesake of Lake Powell) or Oliver Ward (Lyman’s grandfather) efforts to build canal near Boise, Idaho and to irrigate scrub lands into arable land. (not necessarily a good idea — See the Marc Reisner’s 1993 book Cadillac Desert) . Interesting enough Arrowrock Dam was completed in 1914 and it was tallest dam of its time when completed and the sign boasts how important the dam is to the Idaho irrigation systems.

Stegner’s descriptions of the mountains, the towns the people are sharp especially Oliver taking Susan to Leadville in a wagon over a treacherous trek to Leadville. Their brief foray into Michoacán, Mexico was also descriptive. And Stegner also knows how to plot into the narrative with claim jumpers, treacherous journeys and unveiling of the family secret that he uncovers near the end of book.

Quotes and Passages

What really interests me is how two such unlike particles clung together and under what strains, rolling downhill into their future until they reached the angle of repose where I knew them. –Lyman Ward, Page 288

Jackson Benson cites this passage in his Introduction, and I think it gets at the crux of the novel, which is as much about understanding marriages as it is about understanding landforms, landscapes, engineering or engraving. It leaves open the question if Lyman Ward is capable of forgiveness–which perhaps is the central question of his grandparent’s relationship.

The secretary Shelly talking to Lyman Ward about his grandfather: “I think he must have been a lot like you” she said, with her head on one side and that smiling look of speculation on her face. “He understood human weakness, wasn’t that it? he didn’t blame people. He had this kind of magnanimity you’ve got” . “Oh, my dear Shelly”, I said, “My dear Shelly”.

Page 528: The finished sections, so far hardly more than a half mile, sweeps in a great curve around the shoulder of the mountain, eighty feet wide at the top, fifty at the bottom. The twelve foot banks slope back at the “angle of repose”, which means the angle at which dirt and pebbles stop rolling. (it’s like scree, the rocks and dirt that pile up on the side of an eroding mountain face or cliff, that are only supported by their own weight.)

This last Lyman Ward’s wry observation on protests, in response to an advocate for them, his secretary Shelley. (Jackson Benson in the introduction suggests this reflects Wallace Stegner’s view as well). “Civilizations grow by agreements and accommodations and accretions, not by repudiations. The rebels and the revolutionaries are only eddies, they keep the stream from getting stagnant but they get swept down and absorbed, they’re a side issue. “ – Page 576

Final Thoughts

Overall a very good book but it does read a little long. (I tired of Susan’s letters describing her unfulfilling marriage.) It checks the boxes of many of our type of books: well-written, topics include history and history writing, and touches on other books we have read.

Here is Francis’ review on Amazon.

Viewpoints

Karl Kraus wrote: “Grasping the world with a glance is art. Amazing how much fits into an eye.” I believe he would have appreciated this fascinating, nuanced work, which can be mined for many levels of insight. At one level, it sketches a prose picture of western landscapes and its people; at another, it provides a cross sectional look at landforms and the human psyche, at another level it depicts a timeline of history, both personal and public, showing how it unpredictably folds back on itself; and, finally, it asks to what extent to which humankind is able to escape the forces of social pressure, history, genetics and personal bias. This panoramic novel will appeal to anyone with an appreciation for fine writing and interest in the human condition.

https://bookshop.org/widgets.js

Smoke and Ashes: Opium’s Hidden Histories (2023) by Amitav Ghosh

The Economist and The New York Times wrote glowing reviews of the book and Murray had read and liked one of Ghosh’s early novels The Hungry Tide (2003). Coupled with Francis’ personal history on the subject (his wife Deborah’s parents came to the United States from China) this seemed like a good fit. Also, in 2022 we read Barbara Tuchman’s Stillwell and the American Experience in China.

The first half of this book reveals how the Dutch East India Trading Company and the English promoted the cultivation and trade of opium to China. The British were methodical, bureaucratic exploitative in evidence by their two huge opium factories in Patna and Ghazipur.

However, when the British tried to expand to West to the Malwa region they met heavy resistance from local Indian warlords who wanted to keep the opium profits for themselves.

The book goes into detail (maybe too much) about the fighting between the opium warlords and the British, but one of the end results is that Bombay (now Mumbai) was a much more open competitive market with more international involvement whereas Calcutta (now Kolkata) was very regimented by the British. Later we learn about the same international vibe that developed in Guangzhou (aka Canton). This is still somewhat true today.

Midway the book covers America’s involvement in the opium trade with many wealthy families on the Eastern seaboard including the Astors, the Forbes and the Delanos (the grandfather of Franklin Delano Roosevelt). The clipper ships were a big part of their shipping business. Ghosh writes how opium was used as a starter-up money in the banking industry (HSBC). Coincidently Francis and Deborah visited FDR’s Hyde Park home while reading this book. Francis took noted the in the family portrait section that the grandfather’s portrait was noticeably absent.

There is a related cornucopia of topics that have been rolled into this book that captured our interest:

Famous Writers

George Orwell

Page 56: It so happened that Osborne had a colleague called Richard W. Blair who also brought his family to live in a small town in Bihar, where he was posted as Sub-Deputy Opium Agent. It was there, in Motihari, near the Nepal border, that Eric Blair, who later took the name George Orwell, was born in 1903. Orwell was still an infant when his mother, prompted by concerns about her children’s education, left for England with him and his sisters.

Page 77: But George Orwell, as the son of an opium agent and an imperial police officer himself, would have been in a good position to know that the dystopia that he had projected into the future had many analogues in colonial practices as well.

(We’ve read two Orwell books here at GRSG. Earlier this year we read Down and Out in London and Paris and a couple of years ago we read Homage to Catalonia)

Rudyard Kipling and his contemporary and fellow Nobel Laureate the poet Rabindranath Tagore.

Page 69: One Indian who could certainly have visited the Ghazipur Opium Factory was Tagore Kipling’s contemporary and fellow Nobel Laureate, the, who spent six months in Ghazipur, living in a bungalow that had been found for him by a relative of his who worked in the factory.12 During his stay, Tagore and his wife were visited by several relations, including his sister, the writer Swarnakumari Devi, who later composed a long piece about her stay in Ghazipur.13 Their bungalow was close to the factory and through their relative the Tagores met many of the local Bengali residents, most of whom would have been employees of the Opium Department.

Page 70: The distaste that is evident in this passage probably derived from Tagore’s guilty awareness that his own grandfather, Dwarkanath Tagore, had traded in opium, and had even petitioned the colonial government for a share of the reparations that China was forced to pay after the First Opium War.

Economics

Page 15: The duty ranged from 75 per cent to 125 per cent of the estimated value, which meant that the customs duty on tea fetched higher revenues for Britain than it did for China, which charged an export duty of only 10 per cent.7 Largely because of tea, China was consistently among the top four countries from which Britain bought its imports. (this was almost 1/10 of British revenue during the period, and they had a monopoly such that the US colonies could not participate in direct trade).

Also keep in mind that sin taxes are revenue generators for the government.

Cigarette tax in Chicago is $7.16 (State and local), the feds charge $1.01; cost of a pack of Marlboros in Chi: $15—the greater part of this 15 dollars is for tax, not profit.) Washington: The state levies a 37 percent excise tax on cannabis sales that is paid by consumers and remitted by retailers. There are no local cannabis taxes in Washington. Legal sales began in July 2014.

Page 113: Bauer estimates that the costs of producing opium in eastern India amounted to more than a third of the gross revenue that the British earned from it, while the costs of administering the transit tax in the west came to a mere 0.17 per cent. So, for the colonial regime the revenue per chest was the same for Malwa and Bengal opium.

Another important economic observation–the value of being a good dinner guest and host: Page 150: Attitudes of that kind would certainly have created insuperable barriers in Guangzhou’s Foreign Enclave, where socializing over shared meals was essential to the conduct of business. Such meals would almost always have included meat, which in itself would have served to exclude conservative Hindu merchants, many of whom were vegetarian: for them even to enter a house where beef was served meant losing caste.

Diasporas

Page 156: Another diasporic group that became enormously important in the colonial opium trade was the community known as Baghdadi Jews. Page 158: Among the Chinese who ran the opium farms, many belonged to the Peranakan community, a diasporic group with deep roots in the region.67 As with the Parsis (who were Zoroastrians from Iran)and Armenians, countless early Chinese migrants in Southeast Asia were displaced by war, rebellion and political turmoil in their homeland, especially during the tumultuous transition between the Ming and Qing dynasties.

Page 159: Across Southeast Asia, Peranakan merchants controlled many plantations and mines, in which thousands of poor Chinese migrants toiled under terrible conditions: “for he dens and outlets from which the workers bought their opium were often run by the same merchants and syndicates who owned the mines or plantations. (and opium was the only thing making the deadly lives of these workers tolerable–…)

Here Ghosh suggests a questionable panacea: Page 30: Indeed, the only effective means of combating the continuing spread of opioids may lie in forging alliances with other plants—that is by making grassroots psychoactive like cannabis and peyote more easily available. (“and where is the evidence?, we ask)

Colonialism

This topic fits well into other books we have read: Joesph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and more recent Eric Vuillard’s An Honorable Exit a book that centers on French colonialism in Vietnam and to some degree John Foster Dulles support of the Belgian murders of the duly elected president in the Congo.

Calculating the impact of colonialism is not simple, while it was clearly problematic, not all consequences were so and sometimes the colonized shared in the abuse of third parties:

Page 164: The staggering reality is that many of the cities that are now pillars of the modern globalized economy— Mumbai, Singapore, Hong Kong and Shanghai—were initially sustained by opium. In other words, it wasn’t Free Trade or the autonomous laws of the market that laid the foundations of globalized economy: it was a monopolistic trade in a drug produced under colonial auspices by poor Asian farmers, a substance that creates addiction, the very negation of freedom.

While it is difficult to dispute that colonialism was problematic in many ways, it was not as simple as he puts it (colonizer and colonized–page 71: “Page 71: The contrast in the attitudes of Kipling and Tagore, two Nobel Laureates who were almost exact contemporaries, is itself a commentary on the differences in the perspectives of colonizer and colonized:”

Page 117: But the real lesson to be learnt from the commercial world of western India is that political and military support have always been crucial to the flourishing of business and enterprise in the modern era. …Page 118: These practices have remained essential to the functioning of modern imperialism to the present day

Pages 119, 120: In other words, the money generated by Malwa’s opium industry trickled down much deeper, with a larger share of the profits remaining in indigenous hands. A staggering number of ‘princely states’ were sustained by revenues from opium. ‘By the end of the nineteenth century,’ writes Richards, ‘some ninety states engaged in opium production. These ranged in size from the largest in territory and population such as Indore, Mewar, Bhopal, Jaipur, Marwar, Gwalior, Alwar, and Bikaner, to smaller states that dwindled to the size of Sitamau in Malwa with its few thousand inhabitants and one principal town.’

Page 121: The colonial regime’s claim to being the prime agent of ‘Progress’ in the subcontinent was, therefore, completely without foundation.

Page 136 (here is the apology) For the Indians involved in the opium trade, the fact that they were colluding in the smuggling of a substance that was illegal in China, and thereby bringing misery to millions of Chinese, seems to have been even less of a concern than it was to British and American opium traders. As Farooqui notes, no Indian merchants are known to have expressed any qualms about their activities. Yet, it was a Parsi, Dadabhai Naoroji, who became one of the earliest and most important Indian voices to speak out against the colonial opium trade. Born into a poor Parsi family in Navsari, Naoroji became a mathematician, scholar and public figure, both in India and Britain. He spent a good part of his life in London and was even elected to Parliament from 1892 to 1895.37 In his 1901 tract, Poverty and Un-British Rule in India, Naoroji writes: “What Indians would do well to remember these words every time they are assailed by a sense of grievance in relation to China. “

So, it would seem, once the trough of opium trade money filled up, there was no shortage of those willing to benefit from it, regardless of their cities or states of origine and independent of their ethnicity and race. I think the issue has to do with unbridled capitalism, not colonial power, military might or racism–but rather the desire of everyone for money, power and control–however they could be gained–be it monopolies, subjugation of the lower class or caste, and trade routes. The benefits of opening up nations to other and better aspects of civilization, which also followed colonial occupation, cannot be viewed as universally bad.

Heed the title – “A Writer’s Journey”

I am not sure where I heard this expression about this book, but part of the narrative is Ghosh talking about his Ibis Trilogy (2008-2015) a series of historical novels centered around the opium trade (nothing like maximizing your research efforts), but he does talk quite a bit about his other works.

I am not sure where I heard this expression about this book, but part of the narrative is Ghosh talking about his Ibis Trilogy (2008-2015) a series of historical novels centered around the opium trade (nothing like maximizing your research efforts), but he does talk quite a bit about his other works.

What We Didn’t Like About the Book

1) Absence of maps and the absence of an index; 2) The tendency to give too much credit to the quality of Chinese civilization as it existed in the 1800s. While China was a pioneer in the development of civil service examinations, it retained many elements of a feudal society with dynastic families, warlords and internecine struggles but little in the way of innovation or acceptance of other cultures and learning. My mother-in-law’s grandmother (born in the 1800s in China) had bound feet and was the daughter of the 4th wife of a warlord. 3) The author tries to blame Europeans for denying their role in spreading infectious diseases (such as smallpox), this is ludicrous because “Germ Theory” was first proposed as a possible explanation for disease in 1878!; 4) The author postulates some sort of mystical role for poppies as a plant with agency, a concept that is little better than the whimsical horror satire: “Little Shop of Horrors”. The author should have simply used the notion as a metaphor. 5) It is annoying to realize that one of the key chapters in the book is available on-line as an extended published essay, one that details the involvement of prominent New Englanders in the USA in the opium trade:

What We Did Like About the Book

1) The clear recognition that opiate supply is what drives its demand. It is one of the few known commodities on earth that violates the typical supply and demand relationship. 2) The recognition that special rules are needed to curtail its abuse, as indicated by his recognition that those states (Idaho, California, Texas, Illinois, and New York, states which could not differ any more on geographical or political measures) which had restrictions on prescription writing for narcotics were the states that had the least problems with the opium epidemic in the last decade. 3) The author rightly is amazed by the ease with which the Sackler family seduced expert institutions and professions which were supposed to safeguard health and pharmaceuticals in the USA–which include medicine, law, the FDA and policing; and 4) His thoughtful suggestion that academics and other experts are often drawn to faddish new ideas that go against traditional teaching, in this case, the faddish new idea was that narcotics were safe and grossly underused by the medical establishment and FDA and that substance use should be legally tolerated and rarely subject to disciplinary action.

And finally when you think about it, Ghosh’s book and does invite discussion. He is not a perfect, but the writers has plenty to say and for the reader to think about. You can learn a lot from reading Opium’s Hidden Histories (while watching Michael Woods’ PBS documentary on China and visiting Hyde Park.)

We finish with Francis’ four-star view Amazon Review

This book enlivens the suppressed economic history of opium with well researched corroborative detail. It begins with British colonial powers in the 1800s who standardized its production in India and then experienced its wealth generating properties in China. This led to a feeding frenzy which even attracted well-connected Americans. In choosing the Far East over the West, where the saying advises them to go, these young men acquired riches that made their names famous: Forbes, Brown, as in the University, and Delano, as in FDR’s grandfather. The book makes painfully striking parallels with the modern day Sackler family and wisely points out how recognizing of the hypocrisy needed to hide the opium economy likely influenced the writing of Eric Blair (a.k.a. George Orwell) and Rabindranath Tagore. Oddly, the author suggests that poppies have agency, along with mushrooms and cannabis (but he ignores tobacco), and posits, without evidence, that their qualities, which border on ‘mystical’, could mitigate the lure of opium. Two chapters wander off on unrelated themes: a “Lost Cause” lament about British military success and a well-argued but superfluous deconstruction of classic English gardens. While the book is imaginative, well written and instructive, this reader could have done without its gratuitous asides.

https://bookshop.org/widgets.js

The Light Eaters: How the Unseen World of Plant Intelligence Offers a New Understanding of Life on Earth (2024) by Zoë Schlanger

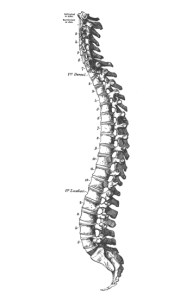

This book arrived at GRSG’s doorstep from several directions. Book reviews, an excerpt in The Atlantic and one of the regulars who visits Murray’s book pop-up at the Freedom Farmer’s Market recommended it. It worked for us on several levels. Francis is always interested in the workings of the brain, nervous system and intelligence and I do some gardening. Many of Schlanger’s investigations helped me further understand some of the day-to-day occurrences that I have experienced as a gardener.

This book arrived at GRSG’s doorstep from several directions. Book reviews, an excerpt in The Atlantic and one of the regulars who visits Murray’s book pop-up at the Freedom Farmer’s Market recommended it. It worked for us on several levels. Francis is always interested in the workings of the brain, nervous system and intelligence and I do some gardening. Many of Schlanger’s investigations helped me further understand some of the day-to-day occurrences that I have experienced as a gardener.

For example, on Page 114 Schlanger explains how climbing vines (like my morning glories, my peas and cucumbers) know where to climb. As a gardener I know that I have to put something nearby for them to climb on, but do I have to actually place the new vines in the proper position? No. I now know that there is a theory that plants utilize a kind of echolocation (sonar –like bats) to sense where to position themselves to grab on something solid.

“So that’s how they do it!” I exclaimed to myself.

The Light Eaters reminds me of some of the books I sell on attracting good insects, and companion plants. But the most similar book to The Light Eaters is Merlin Sheldrake’s very popular book on fungi The Entangled Life. Francis pointed out in his comments that Schlanger has passages on the constant interaction between plants and fungi. He references pages 206 – 208 from the book which includes a mentioning of Sheldrake:

“In some cases fungi has been found to ‘charge’ a plant more carbon in exchange for the transfer of a smaller amount of phosphorus when the mineral is scarce, and to do the opposite when phosphorus is abundant. (A law of supply and demand.)…Yet plants have their own strategies to get the most out of these fungal associations: researchers found that plants can preferentially direct carbon toward fungal strains that are inclined to supply them with greater quantities of phosphorus.”

Most Instructive Passages

We both agreed that this bit of knowledge could be quite handy when we chat with our neighbors about why roots attract underground pipes:

“This would likely not surprise a plumber. Plumbers are accustomed to the frustrating phenomenon of tree roots bursting through sealed water pipes. Cities spend millions each year repairing municipal pipes punctured by “root intrusion.” Most instructive; particularly the part about roots sensing running water in pipes—even without moisture.” Page 112

Another passage that captured both of us was her appreciation of the intricacy of seeds.

Seeds take the gamble of their lives when they decide to emerge. They can often wait months or years for the right conditions. Those conditions are not only things like moisture and heat; their neighbors are also variables that can impact a seed’s potential survival into plant adulthood. Page 205 (like the Parable of the Sower:

The Parable of the Sower is a parable told by Jesus in the Bible in Matthew 13:1-23, Mark 4:1-20, and Luke 8:1-15. The parable is about a farmer who sows seeds in different places, and the results vary depending on the type of soil.

More Fascinating Passages

Francis selected these two:

- The slug digests the cells but keeps the chloroplasts within them intact, spreading them out through its branched gut. Now the slug itself has turned from brown to a brilliant green. After a few algal bubble teas, the slug never needs to eat again. It begins to photosynthesize. It gets all the energy it needs from the sun, having somehow also acquired the genetic ability to run the chloroplasts, eating light, exactly like a plant.” Page 227

- “To develop cultivars in crop breeding, farmers select for the most ‘vigorous’-looking individual plants in a field. But these are actually the most competitive individuals. The plants with more altruistic tendencies will be more reserved, in that they will tend not to grow aggressively into their neighbor’s sun space. (Fascinating observation which has relevance to hiring practices…)… If a farmer were to instead select altruistic plants early in the breeding process, it could steer the crop toward allocating fewer resources into competing for space, therefore presumably putting more energy into reproduction…On the flip side, aggressive plants are useful when the aggression is directed to plants outside the cultivar—non-kin plants, including weeds. Choosing the plants adept at helping their neighbors but fighting off intruders might ultimately result in a highly resilient cultivar. Page 204

Murray’s memorable passage is one of fear.

This involves invasive species (like the Morning Glory which admittedly, I grew intentionally on my deck). In a late chapter on Inheritance, Schlanger writes about invasive species, a word that it is tossed about a lot in community gardens. (“If he doesn’t take out that Wisteria in his plot, I am gonna do it for him.” threatens one of my fellow gardeners.) But Schlanger writes:

This involves invasive species (like the Morning Glory which admittedly, I grew intentionally on my deck). In a late chapter on Inheritance, Schlanger writes about invasive species, a word that it is tossed about a lot in community gardens. (“If he doesn’t take out that Wisteria in his plot, I am gonna do it for him.” threatens one of my fellow gardeners.) But Schlanger writes:

“Invasive species have often been maligned as more aggressive, ruthlessly competitive. These are strangely moralizing concepts to put on a plant, when you think about it. The words we use for invasive species are very often unsubtle in their xenophobia, matching nativist language. We call them “aliens” and drape tropes on them about being unnatural in their abilities, aggressive by nature, like diseases on the land…We’ve caused–and we are still causing!-most of these invasive species to show up in new places to adapt to new scenarios and locations. We literally bring them there. It’s even stranger to fault a plant for its successes with this fact in mind.”

In the next paragraph she gives her personal losing battle with the invasive Japanese knotweed as plant she describes as “no plant more successful on the planet, or more hated.” She gives the details of how it took over a backyard that she rented.

And we finish with Francis’ four-star Amazon Review

Flora and Fancy

In 1919, Eden Philpotts wrote, “The universe is full of magical things, patiently waiting for our wits to grow sharper.” This book, in elegant prose, highlights numerous remarkable discoveries about plants and their interactions with the environment in many ways hitherto unknown. When the author describes them, in essence, the who, what, where, and when, the book is marvelous and accounts for about 80% of its content. Did you know, for example, that plants develop complex interrelationships with fungi in the soil that involve exchanges of carbon and phosphorous subject to the rules of supply and demand? The remainder of the book, an attempt to answer why plants act the way they do, is a discourse on the possibility of plant sentience, a bit of fruitless sophistry. The alternative, modest understatement and skepticism, would have encouraged readers to develop a less prescriptive, and more personal appreciation of plants and their role in the ecosystem. Still, if taken with a pinch of salt, the book is informative and a great resource for plant lovers.

https://bookshop.org/widgets.js

From Empire to Revolution: Sir James Wright and the Price of Loyalty in Georgia (2024) by Greg Brooking

Francis recommended this book, which seemed like a good idea since the GRSG is having its annual meeting in Savannah in October.

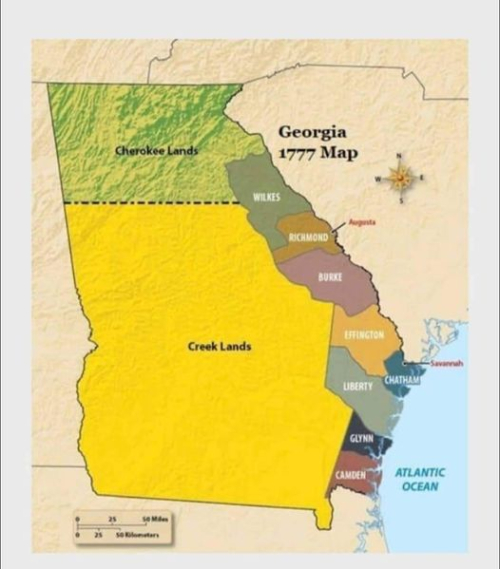

Sometimes it slips one’s mind that Georgia was one of the original thirteen colonies. James Oglethorpe founded the British colony of Georgia in 1732 – in part as a buffer between the Carolinas and Spanish held Florida. However, not only this book is about James Wright (1716-1784) who became the governor of Georgia, but Brooking adeptly uses Wright’s life in Georgia as the vehicle to hold the twenty-five year historical narrative of the early days of Georgia together. Wright arrived in 1760 and he remained loyal to the Crown until he forced to leave Savannah as the residents of Georgia demanded to be free on British control, which came to a head in 1775, coinciding with the beginning of the American Revolutionary War. Wright returned/escaped to England for several months but because of his experience returned to the Georgia and was present in the Battle of Savannah before forced to leave again in 1781 after the defeat of the British at Yorktown.

The first half of the book covers Wright’s rise to power and his accumulation of wealth through his plantations and the enslavement of the blacks from Africa. Brooking neither apologizes for Wright nor does he gloss over the high percentage of the populations of Georgia was black (~40% during Wright’s tenure) and its effect on the importance economically to the British empire. Brooking writes:

“His (Wright’s) lifelong quest for familial redemption, private wealth, and, perhaps most importantly, personal respect was grounded in a deep conservatism that required, according to historian Bernard Bailyn, “a stable world within which to work, a hierarchy to ascend, and a formal, external calibration by which to measure where he was.”- page 229

Wright was skilled in his relations with the Cherokee and Creek Nations, which you can see from the map dominated the geography of Georgia. Wright managed the trade with Cherokees, but there were unscrupulous and vicious traders (known as Crackers) that led to most of the unrest in the region before a full-scale war broke out between the British-Loyalists and the American rebels and the French. Make no mistake this was a full scale civil war but hidden in the history books because the numbers of combatants were nothing to the scale of the 1861-65 War Between the States. Brooking writes:

“And during a vicious civil war, it is easy to understand the necessity of riding the fence. One historian characterized the civil war in Georgia as a “fratricidal conflict characterized by ruthlessness and undisguised brutality.”…Another stated that he “was not prepared [to encounter the depth of] the violence and savagery of the partisan warfare” in the Lowcountry. Additionally, he wrote, “The patriotic gore written by contemporaries depicting the brutish villainy of the Tories I had more or less dismissed as gross exaggerations. It was not. What was exaggerated was the purity and nobility of our patriotic ancestors . . . [who] were every bit as vengeful as their enemies.” Pages 169-171

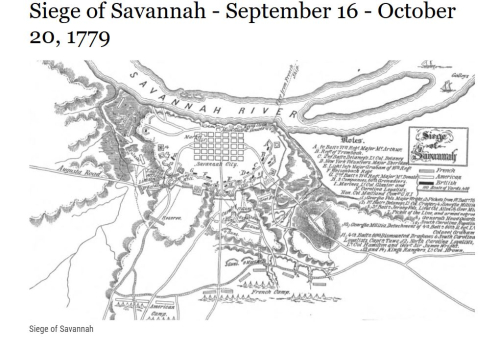

Battle of Savannah

Admittedly, neither one of us knew anything about the Battle of Savannah, but it was “one of the bloodiest during the revolution, exceeded only by Bunker Hill in sustained casualties by one side.” The Loyalists and James Wright were cornered in Savannah with French and American rebels closing in them, but the Loyalist prevailed, but only for a few more years. One takeaway from the book is the diversity of the combatants (a regular Democratic National Convention with muskets):

The battle also may have been the most ethnically and racially diverse of the Revolutionary War. Redcoats, Scottish Highlanders, Hessians, African slaves, Cherokee and Creek Natives, and Loyalists from Georgia, the Carolinas, New York and New Jersey were led by a Swiss-born commander, and all fought under the British banner. Matching up against this foe were French grenadiers, American rebels, Irishmen, Polish hussars, Afro-Caribbean mulattos and Black troops.

Well Titled

As you begin reading this book you think of it as a biography of James Wright, but Brooking’s scope is much wider than that. By the final pages you somewhat find yourself empathizing with the Loyalists (not necessarily Wright) who were eventually driven from their homes or forced to change their allegiance to a movement they did not believe in to survive — thus the significance of the second part of the title “And the Price of Loyalty in Georgia.”

Other Excerpts of Note

“For the most part, James Wright held the common view of Native Americans during his life: they were savages in need of civilization. His view of backcountry whites was only marginally better. He referred to settlers as ‘a set of almost lawless white people who are a sort of borderers and often as bad if not worse than the Indians.’ …. (page 9)

“Famed author, lexicographer, and bon vivant Samuel Johnson once quipped that oceanic travel was akin to being tossed into jail but with the added prospect of being drowned……There was truth to Johnson’s witticism, however, as 20 percent of eighteenth-century Atlantic voyages ended in disaster. Twenty percent! ….. (page 57) Wright’s wife Sarah and his daughter perished on a 1764 voyage to England.

First, Wright accurately predicted the dire long-term consequences of Parliament’s repeal. Second, this prediction was rooted in Wright’s seemingly inherent paranoia about threats against parliamentary authority, which in turn threatened his own power. Sometimes paranoia can be perceptive prescience”. Page 113

Final Thoughts

You cannot discount how slavery played a part in it (on page 147 the author provides an inventory of Wright owned eight plantations which was being worked by a total of 375 enslaved black men, women and children). And as the historian Bailyn described Wright “as a man who spent a lifetime relentlessly accumulating land wealth, status and power.)”

One of the strengths of the book that we both agreed upon is that Brook avoids the common pitfall of history writing by imposing of tainting current values on past events. We end with Francis’ five Amazon review:

The Revolutionary War–Unframed:

The author of this biography, Greg Brooking, un-swayed by current conflicting narratives of its root causes, chronicles how a key individual experienced the revolutionary war. James Wright was born in England, trained in law and moved to Charleston SC where he climbed the social ladder and cleared a tarnished family name through his legal acumen, marriage, and the acquisition of plantations with enslaved workmen. This led to his royal appointment as British governor of nearby Georgia, and his involvement in an escalating series of disputes involving native American tribes, backwoods settlers, landed gentry, and elected and sometimes dissolved Georgia assembly, British politicians, and the increasingly anti-British sentiments of the population. Perhaps better than any other Georgian, he understood the disparate motives of these parties, which augmented his credibility, but, his implacable loyalist stand, which kept Georgia as the last colony to shed British occupation, ultimately cost him his new world wealth and forced his return to England. For many rank-and-file colonists of Georgia ideology was a luxury they could ill afford. For them, the decision on which side to join was delayed until it was forced on them and based on the likelihood of reprisals (which were not infrequent) or rewards from the forces that were nearest, and which shifted with the conduct of the war. Those interested in a grass roots history of the Revolutionary War or colonial life in Georgia will find this book of interest. Those looking for a paean to liberty, or an exposé of blatant hypocrisy will be disappointed, as the author, content with primary sources, only relates how the people living then saw events, without the bias or benefit of how we see it today.

https://bookshop.org/widgets.js

Hunger (1890) Knut Hamsun

This was a selection that came about because of Murray’s trip to Europe in the summer of 2024, which included stops in Oslo (shoreline shown below) and Stockholm. In preparation for his trip to Norway Murray read some of the works of their internationally known writer Karl Ove Knausgaard (My Struggle Books 2 and 3). See Swedish Book Notes.

Hamsun is mentioned several times is My Struggle, and Knausgaard himself is ticked off when a guest at this dinner party taunts him by calling him Hamsun. I was curious so I purchased a copy of Norwegian Nobel Prize Winner’s novel at The English Book Shop in the Södermalm District of the Stockholm.

Hamsun is mentioned several times is My Struggle, and Knausgaard himself is ticked off when a guest at this dinner party taunts him by calling him Hamsun. I was curious so I purchased a copy of Norwegian Nobel Prize Winner’s novel at The English Book Shop in the Södermalm District of the Stockholm.

Earlier this year Francis and I read another book about an impoverished writer in Europe–Down and Out in Paris and London by George Orwell. Moreover, we include from time to time some of the classics (Homer, Faulkner, Stendhal, Mary Shelley, Laurence Sterne) in our reading rotation.

Defies Description

Set in Kristiania (the name of the city before it became Oslo) This novel defies description because not much goes on. In the afterword by Paul Auster (the Canongate edition translated Sverre Lyngstad) describes Hunger:

“It is a work devoid of plot, action and but for the narrator character. By nineteenth-century standards, it is a works in which nothing happens…He gives an account only of the hero’s (a writer) worst struggles with hunger…Historical time is obliterated in favor of inner duration. With only an arbitrary beginning and an arbitrary ending, the novel faithfully records the vagaries of the narrator’s mind, following each though from its mysterious inception through all its meanderings, until it dissipates, and the next thought begins.”

Another way this book is described as the little brother of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment (1866) or his novella Notes from the Underground (1864). Francis recalls reading Notes with its manic narrator. Hamsun may have been an influencer of Albert Camus, Franz Kafka and John Fante, (according the book blurbs on the back cover) but this signature work appeared after the publication of Crime and Punishment and Notes.

Too bad for me. I am a big fan of Camus and Fante and Orwell’s Down and Out, but this book not so much. On the other hand, as he often does, Francis encouraged me to finish it after our discussion. He admitted at the book at times was a slog, but one passage did remind of a quote from Primo Levi about discovery:

crashing around in a cave, with the ceiling progressively narrowing as you move forward, until, abashedly you climb out backwards on hands and knees….

Though not in the same class as Primo Levi, but I think they both authors would agree that discovery involves exploring a lot of blind alleys. Hamsun’s maze, however, was the result, not of ignorance or nature’s complexity, but of his own cognitive machinations.

It also reminded Francis of another quote that explains his take on Hamsun from Abba Eban (1915-2002) former Israeli Foreign Minister – History teaches us that men and nations behave wisely once all other alternatives have been exhausted.

Another line from Hamsun reminded me (Murray) of something that might have been written by Orwell: The intelligent poor individual was a much finer observer than the intelligent rich one. But those kind of insights were rare.

As our tradition we finish with Francis’s four star Amazon review:

A world of woe, or whim?

Soren Kierkegaard once wrote: “If I were a pagan, I would say that an ironical deity gave man the gift of speech so that he may be entertained by their self-deceit.” In “Hunger” the author, Knut Hamson, demonstrates the inconsistency of human reason by showing how easily one’s stream of consciousness slips its banks on an impulse, particularly in those enfeebled by isolation and malnutrition. Surprisingly in this short novel, the mental meandering of the protagonist entertains the reader, perhaps because it recapitulates the cerebral gymnastics many readers have experienced in response to the vicissitudes of daily existence. Despite the travails of the main character, his endless generation of possible solutions may not be in vain as he struggles to find a way out his self-imposed labyrinth of conflicting misdirection. Recommended for unhurried readers interested in introspection’s pitfalls and potential.

https://bookshop.org/widgets.js

The Book-Makers: A History of the Book in Eighteen Lives (2024) by Adam Smyth

We both read reviews of this book and it sounded interesting so we went for it. Overall it was a good choice –but not without its flaws. For Murray, it reminded him of his personal experiences on the periphery of book creation and book selling. Here’s a chapter by chapter run down.

Introduction

On page 5, Smyth commentary about the history of books/printing reminded Murray of the Marshall McLuhan’s dictum that “at first new media will copy old media” before it finds its own space and stride. Think how early television mimicked radio and how digital newspapers mimicked and still do provide electronic print versions of their content.

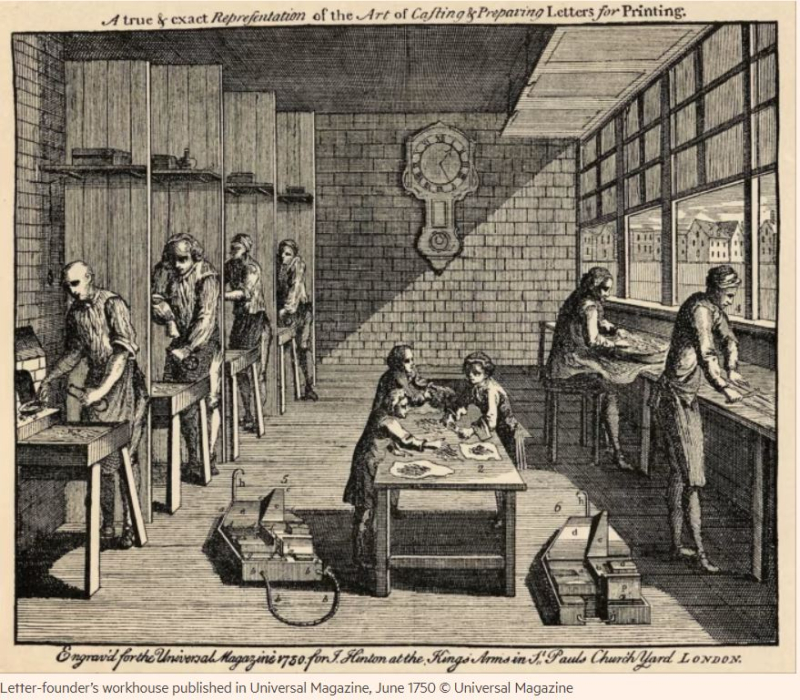

Chapter 1 Printing: Wynkyn de Worde

Page 8, We learned what a colophon is.