GRSG 2025 Reading Notes

The Gravity’s Rainbow Support Group (GRSG) began in June 2020 as a “reading group” of two people. It was a support mechanism to plow though Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (a book you should never try to read alone) during the pandemic. The GRSG took some of the difficulty out of reading this challenging book and provided a way to keep two now-retired college chums (from Indiana University) Francis Walker of Winston-Salem, North Carolina and Murray Browne of Decatur, Georgia in touch. Basically, we decided to keep this good thing going. Undaunted we take comfort in the quote by Alfred Whitehead, written in 1955:

A man really writes for an audience of about ten persons. Of course if others like it, that is clear gain. But if those ten are satisfied, he is content.

This page is the sixth installment of our reading-discussion notes of books we assigned ourselves in 2025. Our reading notes include favorite quotes and passages and some of our discussion about the book. Don’t expect coherent prose or well thought out arguments, but our musings may provide insights to your own understanding and enjoyment of these books. We finish each posting with one of Francis’s sterling Amazon reviews.

Here are the lists of books read and discussed in previous years:

2020 Reading Notes Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon; The Denial of Death by Ernest Becker; Pnin by Vladimir Nabokov

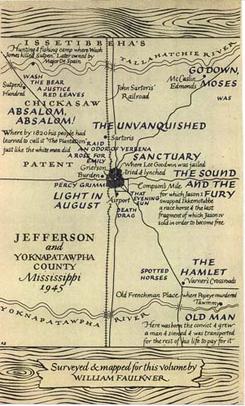

2021 Reading Notes The Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War by Drew Gilpin Faust; Absalom, Absalom by William Faulkner; Stilwell and the American Experience in China, 1911-1945 by Barbara W. Tuchman; Cultural Amnesia by Clive James; The Periodic Table by Primo Levi; The Historian’s Craft by Marc Bloch; An Inventory of Losses by Judith Schalansky; Homeric Moments: Clues to Delight The Odyssey and Illiad by Eva Brann; Homage to Catalonia by George Orwell

2022 Reading Notes The Age of Anger: A History of the Present by Pankaj Mishra; Mountains and a Shore: A Journey Through Southern Turkey by Michael Pereira; The Life and Opinions of Tristam Shandy Gentleman by Laurence Sterne; Grant by Ron Chernow; The Innocents Abroad by Mark Twain; The U.S.A. Trilogy by John Dos Passos (The 42nd Parallel, 1919, and The Big Money); Under the Net by Muriel Spark; Two Wheels Good: The History and the Mystery of the Bicycle by Jody Rosen; Red and Black: A Chronicle of 1830 by Stendhal.

2023 Reading Notes A Path Lit by Lightning: The Life of Jim Thorpe by Robert Maraniss; Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad; Algorithms to Live By: The Computer Science of Human Decisions by Brian Christian and Tom Griffiths; Force: What It Means to Push and Pull Slip and Grip Start and Stop by Henry Petroski; On Bullshit (2005) by Henry G. Frankfurt; Dubliners by James Joyce; TransAtlantic by Colum McCann; Regeneration by Pat Barker; Under the Eye of Power: How Fear of Secret Societies Shapes American Democracy by Colin Dickey; The First World War by John Keegan; Frankenstein by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley; Galileo and the Science Deniers by Mario Livio.

2024 Reading Notes Down and Out in Paris and London by George Orwell; An Honorable Exit by Éric Vuillard; Poor Things by Alasdair Gray; I Never Did Like Politics: How Fiorello La Guardia Became America’s Mayor and Why He Still Matters by Terry Golway; Angle of Repose by Wallace Stegner; Smoke and Ashes: Opium’s Hidden Histories by Amitav Ghosh; The Light Eaters: How the Unseen World of Plant Intelligence Offers a New Understanding of Life on Earth by Zoë Schlanger; From Empire to Revolution: Sir James Wright and the Price of Loyalty in Georgia by Greg Brooking; Hunger by Knut Hamsun; The Book-Makers: A History of the Book in Eighteen Lives by Adam Smyth; The March of Folly: From Troy to Vietnam by Barbara Tuchman; Death Glitch: How Techno-Solution Fails Us in This Life and Beyond by Tamara Kneese.

And now we move on to 2025:

Billy Budd by Herman Melville

Written near the end of his life Herman Melville’s (1819-1891) Billy Budd was subjected to various minor revisions posthumously. Although Melville is now considered part of the canon of 19 th century American novelists with his leviathan Moby Dick Melville’s influence had sunk into oblivion until 1925 when D.H. Lawrence revived it.

Written near the end of his life Herman Melville’s (1819-1891) Billy Budd was subjected to various minor revisions posthumously. Although Melville is now considered part of the canon of 19 th century American novelists with his leviathan Moby Dick Melville’s influence had sunk into oblivion until 1925 when D.H. Lawrence revived it.

On occasion the GRSG has included some of the classics —The Odyssey and Tristam Shandy, and Frankenstein in its reading repertoire. Why we selected Melville in this instance remains a mystery, but we did temper our commitment by selecting the novella.

Plot

Billy Budd, aka The Handsome Sailor is “a fine specimen of the genus homo who in the nude might have posed for a statue of young Adam before the fall” writes Melville (Chapter 18). He is in his early 20s, illiterate, naïve, and ignorant. He has a stutter which flares up when he becomes anxious. Often he attempts to hide his speech impediment by remaining silent in key moments. He is popular among his shipmates, except the insidious Master-of Arms-Claggart, whose is described as having “a conscience as being but the lawyer to his will, made ogres of trifles. ( Melville echoes a theme of German Philosopher Hans Vaihinger (1852-1933) who says that the mind waits hand and foot on the will). Claggart is envious of Billy (for some reason he didn’t like the cut of Billy’s jib) and falsely accuses him of mutiny. (Since the book is set around the Nore Mutiny of 1797, the British Admiralty is very sensitive about mutinies). After a brief naval engagement with a French frigate, Billy is brought before the educated, respectable Captain Vere, where Claggart accuses the unsuspecting Billy of treason. Provoked, the Handsome Sailor lashes out and punches the Master-of-Arms hard enough to kill him.

Making a short story shorter – Billy is found guilty of murder by a trio of ship officers and is hung at dawn the next morning.

End of story? Hardly, there’s much more to it.

The Writing

Reading Billy Budd, it understandable why Melville was considered a master of the 19th century fiction. The descriptions and thoughts of the main characters and an account of life in the British navy, which was the lifeblood of the empire, are impressive.

Here Melville describes the common seafaring man of the day:

“Their honesty prescribes to them directness, sometimes far-reaching like that of a migratory fowl that in its flight never heeds when it crosses a frontier.” (Ch. 8)

Melville reinforces the somewhat larger truth about those with careers in the military – they are really taught not to think for themselves but to follow orders. He writes

“Every sailor, too, is accustomed to obey orders without debating them; his life afloat is externally ruled for him; he is not brought into that promiscuous commerce with mankind where unobstructed free agency on equal terms- equal superficially, at least- soon teaches one that unless upon occasion he exercise a distrust keen in proportion to the fairness of the appearance, some foul turn may be served him.” (Ch. 17)

Trial

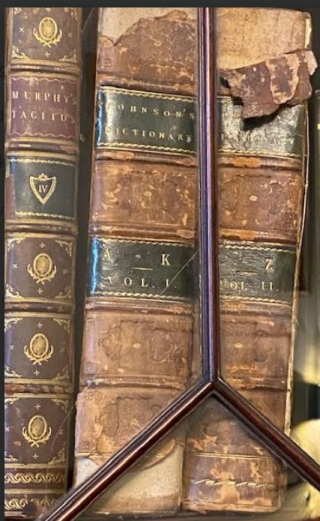

Billy’s hearing is brief but loaded with meaning. First it is presided over by Captain Vere who was an eyewitness to the crime. Vere is portrayed as a fair-minded well-read commander. This description by Melville reminded us that Captain Vere’s taste in books is similar to those books selected by the GRSG.

“With nothing of that literary taste which less heeds the thing conveyed than the vehicle, his bias was toward those books to which every serious mind of superior order occupying any active post of authority in the world naturally inclines; books treating of actual men and events no matter of what era- history, biography and unconventional writers, who, free from cant and convention, like Montaigne, honestly and in the spirit of common sense philosophize upon realities.” (Ch. 7)

Although Captain Vere knew as an eyewitness that Billy’s attack on Claggart was more of an unfortunate accident than something premediated, he recused himself from the hearing. But once the verdict was reached, he justified the death sentence because he was worried that the sailors under his command would think him weak, if he didn’t remain firm in the punishment for mutineers.

Earlier in the book (Ch. 11) Melville suggests that instead of just using legal and medical experts to try someone for insanity:

Why not subpoena as well the clerical proficient? Their vocation bringing them into peculiar contact with so many human beings, and sometimes in their least guarded hour, in interviews very much more confidential than those of physician and patient; this would seem to qualify them to know something about those intricacies involved in the question of moral responsibility; whether in a given case, say, the crime proceeded from mania in the brain or rabies of the heart.”

At the end of the book, a chaplain tends to Billy, but Melville reminds us that chaplains are in the employ of the military not necessarily there to comfort the condemned.

Other sources

Other books were briefly consulted for their commentary of Billy Budd such as Harold Bloom’s collection of essays Interpretations and John Sutherland’s Lives of the Novelists. Interpretations ranging from the underlying homosexuality tensions between Claggart and the Handsome Sailor; Billy has a Christ figure; and Miltonian biblical references. Academics have had a field day with this novella. It served as a reminder to Murray why he never pursued a graduate degree in English.

As been our tradition, we finish with Francis’s five-star Amazon Review.

An Unlucky Tar

Billy Budd is an archetypal figure who, as an innocent young mariner, is non-violently shanghaied on to a ship of war in the early 1800s. The novella describes life among the hierarchy of male characters aboard her and the currents that determine the course of subsequent events. The reader is allowed to act as the judge of members of the crew and the extent to which any of them, and perhaps any of us, should be considered the masters of our souls or simply drifters in a sea of circumstance. Oddly, Melville based his story on a short verse he had previously composed but died with the work unfinished. Others completed it and decided to put the poem at the end in the manuscript, which serves as a touching requiem. Concise, focused and moving, the book is recommended for those wishing to explore the overt and tacit factors that drive human nature.

Tremor by Temu Cole

It is exactly this quality of perceiving truth, extracting it from irrelevant surroundings and conveying it to the reader or the viewer of a picture, which distinguishes the artist. – Barbara Tuchman (one of our favorite historians)

There are three classes of people; those who see, those who see when they are shown, those who do not see – Leonardo DaVinci

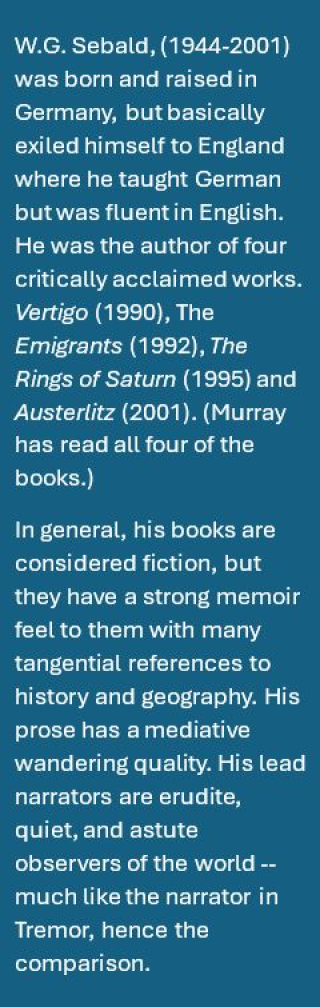

A review in The New York Times Book Review and a comparison to one of Murray’s favorite novelists W.G. Sebald put Teju Cole’s 2023 short novel on our radar.

A review in The New York Times Book Review and a comparison to one of Murray’s favorite novelists W.G. Sebald put Teju Cole’s 2023 short novel on our radar.

The narrator is Tunde a West African man working as a photography teacher at what presumably is Harvard. Through Tunde the plot to meanders (and not necessarily in a bad way) through a number of topics such as art, appropriation of artifacts, and observations about death and the media.

For example, Tunde notes that “a lack of a good photo in the media means you are probably dead.” This longer quote fits right into the book Death Glitch which we read last year, especially when you consider how billionaires are the only ones with the means to “achieve” mortality.

Most of the human beings who have lived and died have left behind them no trace of how they looked, what their voices sounded like, how they moved, what they preferred. It is a vast oblivion but also a relief that we are not inundated with the faces and presences of the innumerable dead. We can move on with our twenty-first-century lives without having to watch videos of every eleventh-century inhabitant of Normandy or Java or Songhay. It was not until the invention and dissemination of photography that it became common for large numbers of people to have their likenesses recorded for posterity, a possibility that had previously been available only to the wealthy and powerful; and it was also only in that era as well with the invention of the gramophone that it became possible for anyone’s voice at all, no matter how eminent, to be recorded and heard after their death. The earlier privilege of remaining uncaptured, of dying with one’s death, was lost. Should the dead move around us like those who haven’t died? Should their presence be more material than those one sees in dreams? (p.52)

Certain chapters are devoted to certain topics and themes.

Chapter 5 – Is a “lecture” on painting that we are assuming Tunder is lecturing his students. Tunder compares J. M. W. Turner’s Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and the Dying (1840) and Landscape with Burning City (1500) by Herri me de Bles.

Chapter 6 – Tunde travels to Lagos in Nigeria and this chapter are mix of short scenes or vignettes center around the people of Lagos such as missionaries, sex workers, school administrators, cloth merchants, a man who tests caskets, and a graffiti artist to name a few. Each scene is self-contained but together they are a composite of city.

Chapter 7 – The theme of chapter 6 continues but switches to the geography of Lagos itself which is a city that has an unusual set of boundaries partially determined by it’s geography. Not only is on the Atlantic Coast but there is a large lagoon that dominates the city center and Victoria Island that is connected by several large bridges.

Impressions

One of our takeaways from the discussion is that Cole’s book is one of impressions. Photographers gather impressions and the resonance of those impressions depends on light, angle, construction of the elements. Writers can be impressionistic as Cole. Plot and character development are not the meat of this book but the narrator/Cole impressions are what make this book a very worthy read.

Some quotes and comments from Francis:

Here is an example of a sort of impression which is used to justify a pre-existing belief:

Page 71: “Another ancestral truth is the way the cells in his body respond when certain music enters him. Everything he would like to say about his experience of the world is encapsulated in certain songs, not popular at the center where he lives, not known to most of the people around him.”

Here are some examples of impressionism, which, by the way, I think apply to anyone who grows up in a major metropolis, be it New York City or Lagos:

Page 77: “Swift decision-making is characteristic of the people of the city where in two seconds and with a single haughty glance the women can determine the true price of a bolt of cloth and declare it either cheap or covetable.”

Page 78: “Throughout the city this talent for accurate and rapid distinctions between flavors, colors, scents, building materials, auto parts, and musical instruments is rampant and extends even to the caskets in which they bury their dead.”

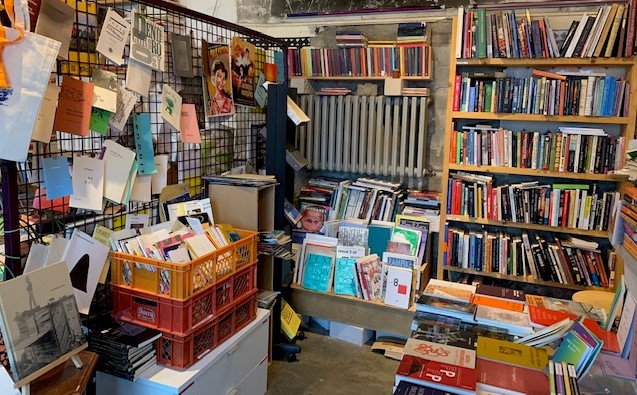

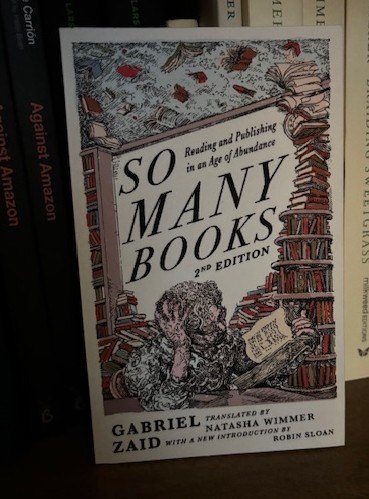

Available at Destination: Books

We wrap up with Francis’s Amazon review

Amazon Review: 4 stars

Does one seism fit all?

This is a story of impressions. The author shows their influence, echoing a theme expressed by Chauteaubriand (1768-1848): “As soon as a verity has once entered our mind, it gives a light which makes us see a crowd of other objects we have never perceived before.” The protagonist, a privileged, Nigerian-American photographer and teacher, approaches the creative process as Paul Klee did: “Art does not reproduce what we see, rather, it makes us see. And, in the book, it is more than just sight, as music, voices, environmental forces, and even intuitions are discussed. While the book demonstrates how such events can be virtually earth-shaking and disrupt comforting notions, the protagonist rarely further explores his or other’s responses to such impressions, sometimes overlooking his tendency toward confirmation bias. One is left wondering if every visual reminder of a tragic event requires an emotional response, if the ability of music to move listeners is truly inherited or simply learned, and the extent to which impressions may sometimes preclude a deeper understanding of human nature. Thoughtful, haunting, and provocative, the book introduces the reader to interesting places and people and eloquently echoes an aphorism of Karl Kraus (1874-1936): “Grasping the world with a glance is an art. Amazing how much fits in an eye.”

The Tell-Tale Heart and Other Writings by Edgar Allen Poe

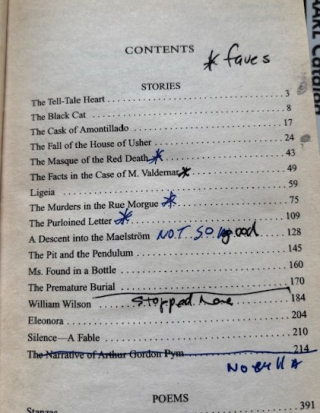

We surprised ourselves by picking another 19th century American author. Like Melville, Edgar Allen Poe (1809-1849) was a writer we read in high school, but neither of us hadn’t looked at since. We agreed to work from the list you see which included some of the standards that we vaguely remembered from our teens.

Overall we appreciated the genius of Poe. His intricate knowledge of certain topics (the dungeons of Spain, the Norwegian Coast and the streets of Paris) even though to our knowledge he never went to Norway or France. Poe suffered from many addictions gambling and alcohol and the effects of disease (he died of tuberculosis) gave him a macabre outlook on life and gave him a brand that has lived 200 years. (We have signed up for a web seminar from our alma mater Indiana University) on that topic.) Moreover, Poe writes with great detail (as does Melville and for Murray he had reread many passages to gather their meaning but one cannot help appreciating their wordsmanship. And learning new words as outré (bizarre) and phthisis (wasting away).

Francis found this passage describing Poe’s process from an essay entitled The Philosophy of Composition (It is rather long, and here he also goes into great detail about writing poems, but this part gives the reader a good idea of what he is after, and it is not a search for the truth or some higher philosophical goal, but rather the technique of creating an effect). Here’s an excerpt:

“I say to myself, in the first place, ‘Of the innumerable effects, or impressions, of which the heart, the intellect, or (more generally) the soul is susceptible, what one shall I, on the present occasion, select?’……”Having chosen a novel, first, and secondly a vivid effect, I consider whether it can best be wrought by incident or tone—whether by ordinary incidents and peculiar tone, or the converse, or by peculiarity both of incident and tone—afterward looking about me (or rather within) for such combinations of event, or tone, as shall best aid me in the construction of the effect.”

Story by Story Quotes and Thoughts

Not only is Poe quotable, but these stories reminded us of other works that we have read here at the GRSG.

The Black Cat

“Who has not, a hundred times, found himself committing a vile or a silly action, for no other reason than because he knows he should n

Note the parallel with this quote from James Geary in The History of the Aphorism: “There are certain mistakes we enjoy making so much that we are always willing to repeat them.”

The Cask of the Amontillado

Revenge not seen since….Billy Budd and reminiscent of the conspiracies that we read about in Under the Eye of Power in 2023.

“I looked at him in surprise. He repeated the movement—a grotesque one. “You do not comprehend?” he said. “Not I,” I replied. “Then you are not of the brotherhood.” “How?” “You are not of the masons.”

The Fall of the House of Usher

Poe describing the misery of its owner:

“…with an utter depression of soul which I can compare to no earthly sensation more properly than to the after-dream of the reveller upon opium—the bitter lapse into every-day life—the hideous dropping off of the veil.”

and in his death throes:

“…..that leaden, self-balanced and perfectly modulated guttural utterance, which may be observed in the lost drunkard, or the irreclaimable eater of opium, during the periods of his most intense excitement.”

This quote reminds us of the book, The Plant Eaters, which we read last year.

(here he is describing the spooky plants that decorate the house in a manner suggesting intent:

“This opinion, in its general form, was that of the sentience of all vegetable things.”

Liegia

“Why shall I pause to relate how, time after time, until near the period of the gray dawn, this hideous drama of revivification was repeated; how each terrific relapse was only into a sterner and apparently more irredeemable death; how each agony wore the aspect of a struggle with some invisible foe; and how each struggle was succeeded by I know not what of wild change in the personal appearance of the corpse?”

Similar to revivification and grave robbing that we read in Frankenstein (in 2023)and Poor Things in 2024.

The Masque of the Red Death and The Purloined Letter

Both crime stories are set in Paris with the same characters.

First there is mediocre French Police inspector, not named, but I think of him as a more serious Clouseau); here Poe gives him this attribute: “…..like him especially for one master stroke of cant, by which he has attained his reputation for ingenuity. I mean the way he has ‘de nier ce qui est, et d’expliquer ce qui n’est pas.’” (To deny what exists, and to explain what doesn’t.)

And then there is brilliant detective Dupin who reminds of how Sir Conan Doyle characterized Sherlock Holmes: “He is fond of enigmas, of conundrums, of hieroglyphics; exhibiting in his solutions of each a degree of acumen which appears to the ordinary apprehension præternatural. His results, brought about by the very soul and essence of method, have, in truth, the whole air of intuition.”

Doyle owes a lot to Poe.

The Premature Burial

“As often happens, when such refusals are made, the practitioners resolved to disinter the body and dissect it at leisure, in private. Arrangements were easily effected with some of the numerous corps of body-snatchers with which London abounds; and, upon the third night after the funeral, the supposed corpse was unearthed from a grave eight feet deep, and deposited in the operating chamber of one of the private hospitals.”

“Among other things, I had the family vault so remodeled as to admit of being readily opened from within….;Besides all this, there was suspended from the roof of the tomb, a large bell, the rope of which, it was designed, should extend through a hole in the coffin, and so be fastened to one of the hands of the corpse.”

As we read about the bell and the robe in: This Republic of Suffering and while we toured a Colonial Park Cemetery in Savannah at the GRSG annual meeting we heard similar stories from our tour guide.

We wrap up with Francis’s four-star Amazon review

Raven-ings

In a somber mood, I dare try to capture the dreary depths of despair dotting the dreamscape of Edgar Allen Poe’s stories. These proceed from one tale of woe to the next, depicting dissolution of the flesh, nightmarish terrors, calculated cruelty, obsessive vengefulness, mystery and manic mayhem invariably highlighting the nuances of premortem agony. While I thrilled with trepidation at the prospect of rereading some of my favorites from childhood: The ‘Pit and the Pendulum’, ‘The Cask of the Amontillado’, and ‘The Fall of The House of Usher’, little did I recall the horror, madness and hideous premonitions of evil they contained. Nonetheless, I trudged on, marveling at the hauntingly familiar notes these macabre stories have since had on literature, motion pictures, and advertising ever since. Oddly, the least morbid of his works: The Purloined Letter and Murders in the Rue Morgue, pioneered the art of detective fiction and provided fertile fodder for copycats, including Arthur Conan Doyle. Recommended for anyone free of squeamishness and interested in Poe, a unique figure in American literature. His complete works, even for those left weak and weary from their perusal, provide plenty to ponder.

P.S. Poe

After finishing our discussion of the Poe short stories Francis and Murray did attend a virtual lecture on February 26th by Indiana University (our alma mater) professor Jonathan Elmer entitled Food for Thought | In Poe’s Wake: Travels in the Graphic and the Atmospheric. It was a 30-minute Zoom lecture followed by a Q & A based on Elmer’s book of the same name.

Its theme was Poe as a brand and how the author was originator of the detective short story and how he has remained relevant almost 200 years later. Two good examples are the Poe detective stories “Murder on the Rue Morgue” and “The Purloined Letter.”

Francis stayed on for the Q & A. Some of the slides were good, but Francis thought that Professor Elmer should have some video clips of some of the adaptations of Poe’s work

Every Man for Himself and God Against All by Werner Herzog

“A well written life is almost as rare as a well lived one.” — Thomas Carlyle 1882

A fellow bookseller first mentioned the Herzog memoir because we were both fans of Herzog’s films especially Fitzcarraldo (1982), Aguirre, The Wrath of God (1972) and My Best Fiend (1999). The latter is Herzog’s reflections about his tumultuous relationship with the screaming Klaus Kinski with whom he made five films.

What made Every Man an interesting read for us is that Francis was not familiar with the films, but I had seen four or five of them over the year. My fellow bookseller even loaned me his set of DVDs. So, our reactions come from two different starting points.

We both agreed that this book is entertaining, insightful (more unintentionally than Herzog trying to impart some great wisdom upon us) and somewhat haphazard. Written in 2022, Every Man is a little too long and could have used some editing. But one of the strengths of this book is Herzog’s voice. It’s the same voice you hear in My Best Fiend and in the audio version of the book which another book friend recommended as an audio book as well. (Herzog is often sought after for narration work).

Here’s is a lengthy sample of Herzog’s voice and demeanor and a hint of what it was like to work with Klaus Kinski:

Dauntless

Soon after Herzog was born in Munich in 1942, his mother when found his crib covered in debris after an Allied bombing and soon relocated Werner and his older brother Tilbert – to the German-Austrian hinterlands. This auspicious beginning was precursor to a Herzog’s life of fearlessness. The family lived in poverty in a hovel with no running water, without adequate heat in the winter and food was scarce. They survived on the indomitable personality of the mother. Herzog writes:

“My deepest memory of my mother, burned into my brain, a moment when my brother and I were clutching at her skirts whimpering with hunger. With a sudden jolt, she freed herself, spun round, and she had a face full of an anger and despair that I have never seen before or since. She said, perfectly calmly: ‘Listen, boys, if I could cut it out of my ribs, I would cut it out of my ribs, but I can’t. All right?’ At that moment, we learned not to wail. The so-called culture of complaint disgusts me. (p. 30)

But the kids knew how to entertain themselves.

“Later, we children played around with carbide and made our own explosives. Setting off a detonation in a concrete pipe that ran under the road was the greatest feeling. We stood on the road above the pipe, and it felt distinctly peculiar to be lifted off our feet by a little explosion.

(Herzog’s father did not live with the family, but did have some influence on Werner intellectually.)

This extreme childhood certainly shaped him into the adventurer filmmaker that he was to become for the rest of his life beginning in his 20s. One story sticks in your mind when he was on Crete and invited to stay with a local when his host gave him the best room as is the custom. Herzog was awakened to the sense that the “something in the room was moving like champagne bubbles. In the light it turned out to be fleas, thousands of them, which I bore uncompellingly so as to not embarrass my hosts.”

This illustrates two important aspects about Herzog and this memoir. The nonchalant attitude he against any challenge by nature (volcano, fire, glacier, ) or anyone whether it be the madman Klaus Kinski or corporate financiers.

In this long clip from You-Tube from My Best Fiend, you get a sense of his calmness in the face of any adversity. And his decisiveness. The excerpts shows Herzog’s ability to make up his mind quickly.

…..(Herzog, after learning of the soon to explode volcano) told him in thirty seconds what was going on in Guadeloupe and asked him if he’d commission such a film. “All right,” he said. “Off you go, but I want you back alive. The bureaucracy’s too slow; we’ll do the contract afterward.” Two hours later, I was on my way to the West Indies. P.41

Creative Process

Passages that give some sense of Herzog’s creative process:

“A few years ago, I met probably the greatest living mathematician, Roger Penrose, and asked him how he proceeded, whether by abstract algebraic methods or by visualizing the problem. He told me it was entirely by visualization.” – page 35 (As in Tremor —which we read earlier this year—this is important: and in our recent discussion of Poe.)

“A few years ago, I met probably the greatest living mathematician, Roger Penrose, and asked him how he proceeded, whether by abstract algebraic methods or by visualizing the problem. He told me it was entirely by visualization.” – page 35 (As in Tremor —which we read earlier this year—this is important: and in our recent discussion of Poe.)

Note: Einstein echoed a similar theme to the one above “On the importance of vision: If I can’t picture it, I can’t understand it. ” Attributed to Einstein by physicist John Archibald Wheeler in John Horgan’s article “Profile: Physicist John A. Wheeler, Questioning the ‘It from Bit’”. Scientific American, pp. 36-37, June 1991.

….in a meeting of all the parties plus lawyers, the representatives of 20th Century Fox were very cordial to me and called me by my first name. Then the suggestion was made that for safety’s sake the film be made in a “good jungle,” i.e., the botanical gardens. I asked politely what they thought a bad jungle was, and the atmosphere instantly froze. From that moment on, I was Mr. Herzog, and I knew I was on my own. -Page 190

“to this day I can only learn from bad movies” – Page 131

“I said that if this film failed all my dreams would be at an end and I didn’t want to live as a man without dreams.” – Page 195

One can appreciate that Herzog kept creative control of his projects with small projects and a small nucleus of film crews. (His younger brother Lucki handle the finances and the rights to Herzog’s work.) Small as we’ve seen recently with 2025 Oscars the two front runners for best picture were made on relatively shoestring budgets.)

And finally, Herzog as a filmmaker is not necessarily restricted by facts. He follows the dictums of other writers. Such as:

Gustave Flaubert “Of all lies, art is the least untrue”

Rabindranath Tagore “ Truth in her dress finds facts too tight. In fiction she moves with ease. Tagore was a chronicler often mentioned in another book we read Ghosh’s book on opium Smoke and Ashes last year.

The French novelist André Gide once wrote: “I alter facts in such a way that they resemble truth more than reality.” Shakespeare observed similarly: “The most truthful poetry is the most feigning.”

Another aspect of his creativity is that Herzog is keen on separating the work from the creator. Herzog talks back to those would criticize him for promoting another’s work because of its merit, instead of damning it for the sins of its creator. He writes:

“My answer here consists of two more questions, though the number could be indefinitely extended. Should we remove the paintings of Caravaggio from churches and museums because he was a murderer? Do we have to reject parts of the Old Testament because Moses as a young man committed manslaughter?” – Page 269.

https://bookshop.org/widgets.js

And in summary here is Francis’ 4-star Amazon review:

A rare slice of life

When Walter Bagehot wrote: “That the greatest pleasure in life is doing what people say you cannot do.” he may have had in mind someone like the filmmaker Werner Herzog. Reading his memoir, which is loosely organized by theme and chronology, I found much to appreciate. The writing is lucid, and Herzog understands that the further he reaches in the past the less his recall should be considered precise. He is fascinated with extremes, in nature and of human behavior, and he obsesses over how to show them to an audience, be it through movies, music, or photography. And for ideas he never had enough time to develop, he describes them for readers perhaps in hope they will take them on. The title of his book “Every man for himself…” speaks to his lack of caution which he admits sometimes imperiled the happiness of those closest to him. However, it underestimates Herzog’s remarkable ability to recruit loyal teammates on his many projects. And the notion that God was against all is ironic, given his numerous near misses with death: severe travel-related illnesses, experimentation with pipe bombs, and encounters with mobs, arrests by corrupt regimes, ski accidents, solo glacier treks, venomous snakes, and decrepit airlines. It appears that someone, if not the Almighty, at least a guardian angel, was on his side. Although the book runs too long, readers will find it unpretentious, engaging, and a startling account of setting seemingly impossible goals that come to fruition. Recommended for those curious about this prolific filmmaker and his eventful life, and for anyone wishing to vicariously experience uncommon places, unusual circumstances, and unorthodox people.

Werner Herzog Interview

By some strange coincidence soon after we finished Every Man for Himself and God Against Us All, 60 Minutes broadcast an Anderson Cooper interview with Werner Herzog, proving once again how GRSG has its pulse on the times.

Somewhere Toward Freedom: Sherman’s March and the Story of America’s Largest Emancipation by Bennett Parten

Our selection of Somewhere Toward Freedom (2025) should come as little surprise because is received prominent reviews in national publications and GRSG has read several books on the Civil War (i.e. Drew Gilpin Faust’s The Republic of Suffering and Chernow’s biography of Grant were two of our favorites). Murray’s interest in the Civil War began when he visited Shiloh with his family as a youth. Coincidently Francis and Murray visited Shiloh in summer of 1999 which include the Shiloh Church where Sherman’s encampment was run over by attacking rebel troops on the morning of April 6, 1862.

If this wasn’t enough there are over twenty entries in Civil War links section of The Book Shopper blog including an excerpt Milledgeville-born composer Alfred Thigpen’s Sherman: The Musical.

As much as I knew about William Tecumseh Sherman, we both knew next to nothing about this aspect of Sherman’s March. A few months ago, the GRSG annual meeting was held in Savannah, which gave us extra appreciation of this time in American history. We even stood outside the Green House of Madison Square in Savannah. Parten writes: “The city’s mayor, Richard Arnold, surrendered the city willingly, and Charles Green, the owner of the Green House, invited Sherman into his home as an honored guest. They weren’t anomalies. Throughout the occupation, Savannah lived up to its now-popular reputation as the ‘Hostess City of the South,’ lulling the soldiers into a false sense of security.”

As much as I knew about William Tecumseh Sherman, we both knew next to nothing about this aspect of Sherman’s March. A few months ago, the GRSG annual meeting was held in Savannah, which gave us extra appreciation of this time in American history. We even stood outside the Green House of Madison Square in Savannah. Parten writes: “The city’s mayor, Richard Arnold, surrendered the city willingly, and Charles Green, the owner of the Green House, invited Sherman into his home as an honored guest. They weren’t anomalies. Throughout the occupation, Savannah lived up to its now-popular reputation as the ‘Hostess City of the South,’ lulling the soldiers into a false sense of security.”

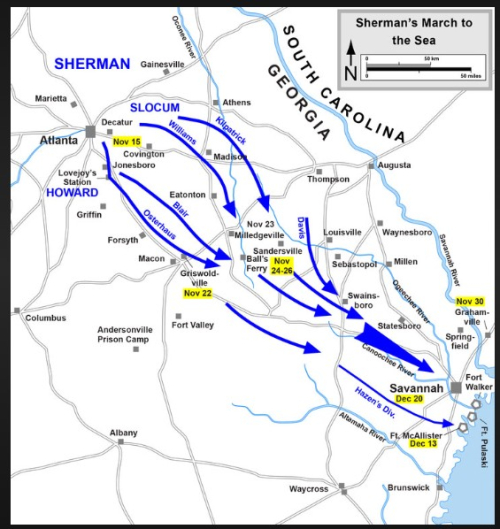

The book does not begin with Sherman’s March to Atlanta, but rather begins after the city caught fire. Sherman had about 100,000 troops after the Atlanta campaign, but dispatched around 30,000 troops back to Tennessee to keep the John Bell Hood Confederates from retaking Tennessee. (This ended badly for Hood with resounding defeats in Nashville and Franklin, Tennessee.)

In November Sherman split his army into two columns the right column led by O.O. Howard that went Madison through Macon and the left column led by Henry Slocum that went through Macon and on to Statesboro. Officially the Sherman’s soldiers were supposed to be “foragers” and their were protocols that were supposed to be followed, but when foragers went rogue there was the more colloquial term “bummers” Parten writes: “so when soldiers arrived at a plantation, the scene devolved into a glorified scavenger hunt. Soldiers checked corner closets and storehouses, interrogated white families, and even went about looking for signs of uprooted dirt. “It was amusing to see the foragers going around prodding the ground with their ramrods or bayonets, seeking for soft spots, according to one Ohio soldiers.

Parten relies on letters of Union officers and troops (remember in the Civil War people wrote letters). He gives accounts of camp life, the taking of livestock and goods from the Georgia countryside (including plantations). Sherman kept his word to “make Georgia howl” and reached Savannah around Christmas of 1864. The Savannah populace wisely left Savannah an open city as the few remaining rebel troops moved on to South Carolina.

But the main thrust of the book is the logistics and the little known history is how the newly freed slaves joined the Army (or followed the Army). Some worked for the Union Army as cooks and builders and others were women and children (refugees) that followed near the Union Army but were subject to deathly harassment by Confederate cavalry. The account of the brutal slaughter at Ebenezer Creek was especially tragic and graphic. A Union general Jefferson C. Davis (yeah, what a name) pulled pontoons over the creek so the Negroes (many women and children) following his column had to cross a frigid creek or face marauding Confederate cavalry anxious to kill them or sweep them back up to captivity.

The book is relatively short and it includes several useful maps. It also spends considerable length discussing the history of Port Royal, South Carolina. Federal gunboats recaptured the garrison early in the war and set it up a community for freed slaves. It received funds from Northern abolitionists and even schools for Black children were set up. But by the winter of 1864-5 freed slaves from Sherman’s March eventually overwhelmed the area and many died from starvation and exposure.

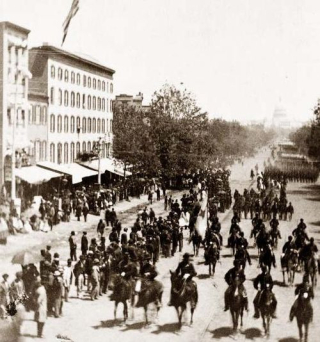

The book closes with Sherman’s Army of the West marching through the streets of Washington D.C. on May 24, 1865 in the Grand Review (more about that here), but Parten adds to it’s historical significance because behind Sherman’s army were the freed families that had followed Sherman from Georgia through the Carolinas and Virginia had joined the parade. Parten summarizes the campaign differently than militarily. He writes, “…like Yorktown, Gettysburg and Selma, Sherman’s March to the Sea was a landmark moment in the history of American freedom.

The book closes with Sherman’s Army of the West marching through the streets of Washington D.C. on May 24, 1865 in the Grand Review (more about that here), but Parten adds to it’s historical significance because behind Sherman’s army were the freed families that had followed Sherman from Georgia through the Carolinas and Virginia had joined the parade. Parten summarizes the campaign differently than militarily. He writes, “…like Yorktown, Gettysburg and Selma, Sherman’s March to the Sea was a landmark moment in the history of American freedom.

Murray’s assessment was that as a Civil War buff he had realized an important gap in his knowledge filled by the Parten book. On the other hand Francis and I learned plenty about Reconstruction from the the Chernow Grant biography we read in 2023.

https://bookshop.org/widgets.js

We finish with Francis’s Amazon Review.

Promises kept and broken

Armies have always attracted camp followers, but none before or since have attracted as many as Sherman’s union troops on their long march from Chattanooga through Atlanta to Savannah and then on to the Carolinas. This book chronicles the stories of the men, women and children fleeing enslavement with this army, the difficult choices they faced, the perils, some fatal, that they encountered, how they assisted Sherman’s forces and how they precipitated the first refugee crisis in American history. The author, taking the oft neglected point of view of the liberated people, faults the northern military, government bureaucracy and charitable organizations for their lack of insight and planning, ill-defined and changing policies, and inability to deliver on promises. The deprivation and suffering of the freed refugees is well documented. The shameful role of southern cavalry in attacking those freed men, women and children who could not keep up on the march is also made clear, as is the egregious behavior of one of a Union leader (oddly named Jeff Davis) who had murdered a former commanding officer and who purposefully ordered the destruction of bridges once crossed by his troops to strand camp followers on river banks, leaving them to the bitter retribution of the southern forces. The author’s most scurrilous comments are reserved for Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s successor, ‘the drunken tailor from Tennessee’, who fought reconstruction. Although the subsequent success, albeit temporary, of reconstruction after this is mentioned, no credit is given to Ulysses S. Grant for its revival. Nor is it possible to gauge the appropriateness of Sherman’s advice to the formerly enslaved persons to not follow his army, as the difficulties of those who stayed behind are left undescribed. The book has a wealth of detail rarely covered in other accounts of Sherman’s march and is an engaging read.

The Pale King by David Foster Wallace

We came about selecting this book in a roundabout way. Murray discussed working on an essay about jury duty while hiking with his friend Bill up in Chattanooga. Bill mentioned this passage (Section 22) in Wallace’s The Pale King (2011) where several characters dialogue about the responsibilities or lack of responsibilities:

We came about selecting this book in a roundabout way. Murray discussed working on an essay about jury duty while hiking with his friend Bill up in Chattanooga. Bill mentioned this passage (Section 22) in Wallace’s The Pale King (2011) where several characters dialogue about the responsibilities or lack of responsibilities:

“Americans are in a way crazy. We infantilize ourselves. We don’t think of ourselves as citizens-parts of something larger to which we have profound responsibilities. We think of ourselves as citizens when it comes to our rights and privileges, but not our responsibilities. – Section 19 page 130

I don’t think of corporations as citzens, though. Corporations are machines for producing profit; that’s what they are ingeniously designed to do. It’s ridiculous to ascribe civic obligations or moral responsibilities to corporations. Page 136

I shared this with Francis and he was willing to take the Wallace book on. In the spirit of full disclosure, I warned him about Wallace—who is best known for his tome Infinite Jest (1996)—And it is for this reason I have steered clear. But one of the tenets of the GRSG and other “top-tier, exclusive” book clubs is that they encourage you tackle books that you normally avoid. Of course we were founded in 2021 on Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity Rainbow, we are not afraid of tough reads like William Faulkner’s Absalom Absalom or Tristan Shandy by Laurence Sterne.

It is worth noting that Wallace (1962-2008)—against his wishes -was often compared to Pynchon in his writing style with much word play, humor, tangents and in the case of Pale King lots and lots of lengthy footnotes. This book was published three years after Wallace’s death (by suicide) by his editor who completed the manuscript.

There are several elements that make this book worthy:

Portrait of Bureaucracy.

Since the main setting is an IRS Regional Examination Center office in Peoria, Illinois. Wallace spares no detail in giving one the sense of This is especially relevant since we read this book in April 2025. In the middle of tax season. Elon Musk’s DOGE and the Trump Administration is in the midst of slashing the IRS workforce by about 20,000 workers. (By no coincidence this book was published around Tax Day in April 2011)

Some examples. There were many to choose from:

Page 17

Tedium is like stress but its own Category of Woe. Sylvanshine’s father, whenever something professionally bad happened—which was a lot—had a habit of saying ‘Woe to Sylvanshine.’

Page 29

IRS WORKER DEAD FOR FOUR DAYS Supervisors at the IRS’s regional complex in Lake James township are trying to determine why no one noticed that one of their employees had been sitting dead at his desk for four days before anyone asked if he was feeling all….

(Here is a recent real-life counterpart–From NBC news in August 2024: )A 60-year-old Arizona Wells Fargo employee scanned into her office on a Friday on what appeared to be an ordinary workday. Then, four days later, she was found dead in her cubicle. Denise Prudhomme, 60, was found dead on Aug. 20 in her office in Tempe, police said. Aug 29, 2024)

Page 82

“one tiny dronelike cog in an immense federal bureaucracy”

Page 84

If you know the position a person takes on taxes, you can determine [his] whole philosophy. The tax code, once you get to know it, embodies all the essence of [human] life: greed, politics, power, goodness, charity. To these qualities that Mr. Glendenning ascribed to the code I would respectfully add one more: boredom. Opacity. User-unfriendliness. (It continues…: Page 85 It is impossible to overstate the importance of this feature. Consider, from the Service’s perspective, the advantages of the dull, the arcane, the mind-numbingly complex. The IRS was one of the very first government agencies to learn that such qualities help insulate them against public protest and political opposition, and that abstruse dullness is actually a much more effective shield than is secrecy. For the great disadvantage of secrecy is that it’s interesting. People are drawn to secrets; they can’t help it. (in honor of the release of the Kennedy files…)

Page 87

Why we recoil from the dull. Maybe it’s because dullness is intrinsically painful; maybe that’s where phrases like ‘deadly dull’ or ‘excruciatingly dull’ come from. But there might be more to it. Maybe dullness is associated with psychic pain because something that’s dull or opaque fails to provide enough stimulation to distract people from some other, deeper type of pain that is always there, if only in an ambient low-level way, and which most of us spend nearly all our time and energy trying to distract ourselves from feeling, or at least from feeling directly or with our full attention…. but surely something must lie behind not just Muzak in dull or tedious places anymore but now also actual TV in waiting rooms, supermarkets’ checkouts, airports’ gates, SUVs’ backseats. Walkmen, iPods, BlackBerries, cell phones that attach to your head. This terror of silence with nothing diverting to do.

Page 242-247

“We are looking for cogs, not spark plugs” – from the IRS recruitment office scene, which is set in the snowbound Chicago during the blizzard of 1979.

Page 430

“It is the key to modern life, if you are immune to boredom there is literally nothing you cannot accomplish.”

Its Midwestern Flavor.

Francis and Murray both hail from the Midwest and we attended Indiana University at the same time. Part of the enjoyment was Wallace’s skewering of academics and his descriptions of the Midwest. Wallace lived in Philo, Illinois which is just outside of Champaign, Illinois where Murray lived for several years—and he drove through Philo many times. (The photo here was from Murray’s 2023 trip to Indiana-Illinois. The “vistas’ haven’t changed much except the wind) turbines

Section 22 which is almost 100 pages long is set in the narrator’s college days in Chicago and applying for a job at the IRS during the aforementioned blizzard in 1979.

One of the better chapters is Section 39 when Stecyk was being tormented in high school Industrial Arts by bullies, which was an apt description of the Industrial Arts classes in Murray’s high school. The agriculture classes in Murray’s high school were much the same. (They even had a boxing ring in the shop area.)

And then this passage from page 117 “You know? By dividing the lawn into like seventeen small little sections, which our mom thought was nuts as usual, he could feel the feeling of finishing a job seventeen times instead of just once. Like, “I’m done. I’m done again. Again, hey look, I’m done.”

An average 1040 takes around twenty-two minutes to go through and examine and fill out the memo on. Maybe a little longer depending on your criteria, some teams tweak the criteria. You know. But never more than half an hour. Each completed one gives you that solid little feeling. (Just FYI, it reminds me of how I used to get through swim team practice in high school–Francis)

“For those who’ve never experienced a sunrise in the rural Midwest, it’s roughly as soft and romantic as someone’s abruptly hitting the lights in a dark room. This is because the land is so flat that there is nothing to impede or granulize the sun’s appearance.” – page 262

Writing and description.

Wallace does not write in terse one-liners his black humor often comes in the description. These are liberally sprinkled throughout the book:

“the average taxi driver, a cynical and marginal species.”

“my mother looked like beef jerky”

“obtuse dullness is actually much more effective shield than secrecy”

“he had a pink timorous face of a hamster.”

Rotting Flesh, Louisiana ( a fictious IRS center) but it sounds like a place House Speaker Johnson comes from .

“She was about as exotic as a fire hydrant and roughly the same shape.”

The auditor with the glass eye at the IRS picnic who popped it out to use his empty socket to open beer bottles.

Minuses

Likewise, there are several elements that make the book problematic when it comes to making a recommendation to other readers. (It is an accomplishment to read, but overall not that difficult — you have to fight through the tedious parts.

It’s Length – 550 pages and often page after pages on one continuous paragraph. No chapter titles (Chapter themselves are referred to as Sections like the Section dividers in a government document.

Writing about boredom and bureaucracy can make for tedious reading especially when Wallace goes down deep rabbit holes of IRS regulations and IRS history. To combat this we found ourselves skimming chapters/sections these sections to move the plot alone. Wait there is no plot!

Remember this book was finished posthumously by his editor Michael Pietsch three years after Wallace’s death by suicide (Hence the descriptions of the mental institution between two characters (Section 46 -74 pages). Francis thinks that Wallace wrote this book where each chapter is a block on the for a wall, but those blocks had not been assembled yet.

Interested in purchasing? See Destination: Books

The Final Verdict

This comes from Francis who admitted the book grew and grew on him the more that he read it and he ended up giving it a Five Star Amazon. No grade inflation from Francis. His last 5-star review was.

Recreational re-creation:

This odd but engaging collection of sketches, of people and relationships in school, at work, and in life comprise this unfinished novel by David Foster Wallace. After his death, his editor selected the best and most easily aligned portions of his extensive draft notes. From them, he created an almost complete work which, if not a true novel, is at least a collection of short stories and vignettes with recurrent themes and characters, all portrayed with accuracy and insight. In them, the unflinching David Foster Wallace shines through, as evident in the following except: “Corporations aren’t citizens or neighbors or parents. They can’t vote or serve in combat. They don’t learn the Pledge of Allegiance. They don’t have souls. They’re revenue machines. I don’t have any problem with that. I think it’s absurd to lay moral or civic obligations on them. Their only obligations are strategic, and while they can get very complex, at root they’re not civic entities. With corporations, I have no problem with government enforcement of statutes and regulatory policy serving a conscience function. What my problem is is the way it seems that we as individual citizens have adopted a corporate attitude. That our ultimate obligation is to ourselves. That unless it’s illegal or there are direct practical consequences for ourselves, any activity is OK.” It remains a mystery how the author intended his sometimes conflicting, sometimes unrelated draft sections to fit in with the overarching backdrop of a fictional 1980s IRS office headquartered in Peoria Il. While the mystery will persist, it may be that he was patiently waiting for the ingredients of his novel, like a chef waiting for a complex recipe to mature, to lead him to a proper solution. Regardless, the bones of his novel are strong and well formed; and his unique style and discerning eye provide plenty of raw material for interested readers to flesh out their own final product, one which may help them better understand themselves and the origins of their impressions of life and the world. Highly recommended.

My (Murray) final thought was that I did feel a sense of accomplishment to read it, but it was not that difficult. Also, my two favorite Wallace pieces remain his essays on the Illinois State Fair “Ticket to the Fair” and “Shipping Out” an account of being on a luxury cruise.

The British are Coming: The War for America, Lexington to Princeton, 1775-1777 by Rick Atkinson

This is Volume 1 of Atkinson’s Revolution Trilogy. The book made our group’s list in a circuitous way. Murray was a big fan and reader of Atkinson’s Liberation Trilogy on World War Two which covered the American campaigns in North Africa, Italy and Western Europe. Murray’s meeting Atkinson twice at book signings did not lessen his admiration. (See “Mini-Review: Remembering Your Father with Rick Atkinson.” ) Given this history, it was no surprise Murray read the The British Are Coming when it first came out in 2019.

Atkinson’s first book of this trilogy did not disappoint either and when Murray heard that Book Two was near publication he put in an advance order through his pop-up book shop Destination: Books. One thing as a bookseller he can really appreciate the exquisite quality of these books: Fine printing, color inserts of paintings of the principals like the two Georges, Benjamin Franklin and paintings of naval battles and ground engagements. (The painting here of Bunker Hill by Edward Percy Moran isn’t one of them.) There are plenty of detailed maps, footnotes and a detailed index. The books are $40, but they far surpass books that cost nearly the same.

Since Francis finished The Pale King weeks ahead of Murray, he suggested maybe Francis would like to take a look at The British Are Coming. After all, last year we read two themed Revolutionary War books last year: Barbara Tuchman’s March of Folly, which devoted a third to how the King George III and his ministers’ miscalculations cost the British Empire the colonies and Greg Booking’s From Empire to Revolution: Sir James Wright and the Price of Loyalty in Georgia. Inspired, the GRSG held its annual meeting in Savannah and visited some of the historical sites including the memorable Pulaski statue in Monterey Square.

Since Francis finished The Pale King weeks ahead of Murray, he suggested maybe Francis would like to take a look at The British Are Coming. After all, last year we read two themed Revolutionary War books last year: Barbara Tuchman’s March of Folly, which devoted a third to how the King George III and his ministers’ miscalculations cost the British Empire the colonies and Greg Booking’s From Empire to Revolution: Sir James Wright and the Price of Loyalty in Georgia. Inspired, the GRSG held its annual meeting in Savannah and visited some of the historical sites including the memorable Pulaski statue in Monterey Square.

Both Atkinson’s books are available at Destintion: Books (support this blog)

Francis finished the book quickly and topped it off with a short five-star Amazon review.

This is a great book deserving of its awards and accolades. It has well-chosen corroborative detail, keeps up a marching pace, which keeps the reader engaged through land and naval battles, and switches points of view, developing simultaneous timelines with adequate depth so the reader feels to be part of each side both militarily and politically. It eschews hagiography and gives a balanced view of the valor, endurance, suffering, unfairness and remarkable characters, rich or poor, foot soldier, king or captain of the times. Recommended for all interested in history and for teens and pre-teens who nurse a spark of enthusiasm for learning the origins of the USA.

This immediately led to our next selection.

The Fate of the Day: The War for America, Fort Ticonderoga to Charleston, 1777-1780 by Rick Atkinson

This is the first time in GRSG history that we read a bestseller within days of its publication AND were able to see the author talk about his book while we were still reading it. Murray attended an event at the Atlanta History Center on May 22nd featuring a conversation with military historian Rick Atkinson (which is how he defines himself).

Atkinson mentioned at the AHC that the book is split into three main sections because it naturally “cleaved into three parts.”

Part I

This begins with the battle for Fort Ticonderoga when British troops led by General John “Gentleman Johnny” Burgoyne and ends with Burgoyne’s surrender after the Battle of Saratoga in October of 1777. Atkinson, in his signature details, describers the two long lines of rebel soldiers bracketing the road. “No laughing or marks of exultation were to be seen among them, ”a Massachusetts colonel said of the American troops. “They had fortitude of mind to bear prosperity without being too much elated. This was one of the early turning points of the war because it fortified France’s involvement as an ally of the Americans. , There is some foreboding in Atkinson’s initial description of the campaign on page 35, “Burgoyne exuded the high-spirited complacency obligatory at the beginning of any military calamity.”

This begins with the battle for Fort Ticonderoga when British troops led by General John “Gentleman Johnny” Burgoyne and ends with Burgoyne’s surrender after the Battle of Saratoga in October of 1777. Atkinson, in his signature details, describers the two long lines of rebel soldiers bracketing the road. “No laughing or marks of exultation were to be seen among them, ”a Massachusetts colonel said of the American troops. “They had fortitude of mind to bear prosperity without being too much elated. This was one of the early turning points of the war because it fortified France’s involvement as an ally of the Americans. , There is some foreboding in Atkinson’s initial description of the campaign on page 35, “Burgoyne exuded the high-spirited complacency obligatory at the beginning of any military calamity.”

Page 232: Burgoyne after his humiliation at Saratoga stayed in British imagination. Kind of like Lew Wallace who wrote the famous novel Ben Hur fter the Civil War erasing the memory is that his Union troops were lost in the woods on their way to the Battle of Shiloh.)

In 1780 he would return to the theater, achieving greater success as a playwright than he ever did as a general. His light opera The Lord of the Manor had a fine run at Drury Lane, and The Heiress was a comic stage sensation, described by an admirer as “one of the most pleasing in our language.” After his death in 1792, at the age of seventy, he was buried in the north cloister of Westminster Abbey beneath a bare slab. (page 232)

Highlight (Yellow) and Note | Page 232: Bernard Shaw’s requiem for Burgoyne

The precise location was soon forgotten, but a century later he would be immortalized, after a fashion, by George Bernard Shaw in The Devil’s Disciple. “Burgoyne’s surrender at Saratoga,” Shaw wrote, “made him that occasionally necessary part of our British system, a scapegoat.”

Adding to our interest in this campaign is that Francis has visited the Saratoga battlefields. There picture of Thaddeus Kosciuszko monument and the boot of Benedict Arnold are significant. Kosciuszko, a master of fortifications built the defenses that made Burgoyne’s escape impossible was little known outside of Revolutionary War buffs unlike Benedict Arnold who was known as traitor to his country. But what is not common knowledge is that Arnold while in fighting for the American was one its best commanders in the field. (The boot is significant because Arnold was wounded in the left leg twice. The second time at Saratoga (hence the boot memorial) but returned to active duty even though one leg was two inches shorter than the other. (Atkinson quipped that he wouldn’t spoil Arnold’s ultimate betrayal. “You’ll have to wait until Book 3.”

Adding to our interest in this campaign is that Francis has visited the Saratoga battlefields. There picture of Thaddeus Kosciuszko monument and the boot of Benedict Arnold are significant. Kosciuszko, a master of fortifications built the defenses that made Burgoyne’s escape impossible was little known outside of Revolutionary War buffs unlike Benedict Arnold who was known as traitor to his country. But what is not common knowledge is that Arnold while in fighting for the American was one its best commanders in the field. (The boot is significant because Arnold was wounded in the left leg twice. The second time at Saratoga (hence the boot memorial) but returned to active duty even though one leg was two inches shorter than the other. (Atkinson quipped that he wouldn’t spoil Arnold’s ultimate betrayal. “You’ll have to wait until Book 3.”

In Part One, Atkinson also give detailed grisly accounts of the battles of Oriskany (New York), Bennington (Vermont) and Germantown, (Pennsylvania). Battles I knew nothing about.

Part II

This section covers the war from the aftermath of Saratoga when the French officially entered the Revolutionary War on the side of the Americans. This is part of War is something we both knew very little about (even though when we read Tuchman’s March of Folly last year, the first third was about how King George III and England totally for a lack of a better term “screwed the pooch” in their policies towards the Colonies.

In these chapters 11-19 covering November 1777 to February 1779 gave details of how the French were more interested in putting it two their mortal enemy the English and tried to pull Spain into the war as well, but with limited success. Most of the French-British battles were naval battles: Ushant Island , a “craggy, fogbound speck of rock twenty miles off the western tip of Britany,” (July , 1778), the Battle for Newport Rhode Island (July-August 1778). Later the opposing fleets clashed in the English Channel, (August 1779) which thwarted France’s invasion of English soil.

John Montagu, the fourth Earl of Sandwich and first Lord of the Admiralty during the War. He was hardworking. Atkinson writes, “working at his desk through meals, he sometimes ate sliced meat between two pieces of break, which he held I one hand while he wrote with the other– the eponymous sandwich. Sandwich was a force in the buildup of the Royal Navy and later patronized the expedition of Captain James Cook who discovered the Pacific archipelago the Sandwich Islands or as it is known now as – Hawaii,

One of many Atkinson’s strengths is how he adds intriguing sidebars mixed with his prose.

“Brigadier General Augustine Prévost—known as Old Bullet Head from a disfiguring wound to the face suffered in the Seven Years’ War—had swept north from St. Augustine, bringing more than seven hundred additional redcoats and loyalist troops, plus a large contingent of loyal refugees who had been hiding in the south Georgia wilderness.”

Then some of us may have heard the Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben who gets credit for whipping Washington’s army into shape at Valley Forge in 1778 (the descriptions of the starvation, sickness and cold in winters at VF in ’77 and ’78 puts the reader in shock on how the Continental army survived.). Here’s an example of how Atkinson adds detail:

When frustrated or irate “he began to swear in German, then in French, and then in both languages together,” his secretary, Peter Du Ponceau, reported. If that failed to bring results, he would tell Du Ponceau, “Come and swear for me in English.” He soon learned two syllables in English—“Goddamn!”— and then a complete sentence: “I can curse dem no more.” Americans, he soon recognized, were unaccustomed to blind obedienc

And then there is the memorable scene when Voltaire returned from exile to meet Franklin. He was near death at the time. “When urged to renounce the devil he (Voltaire) replied, “Is this a time to make enemies?”

Atkinson in Atlanta

Part III

More of the same as Parts I and II: Bloody campaigns like War of the American Frontier when American troops marched up the Susquehanna River to destroy Indian tribes that were allies of the British. This includes destroying crops to starve out their enemies; more naval battles surrounding the Southern ports of Charleston and Savannah which both fell to the British. (Savannah was particular interest of us since we read the From Empire to Revolution: Sir James Wright and the Price of Loyalty in Georgia by Greg Brooking; and visited Savannah last year.

A couple of related observations that made this book a challenge to read (not because it was not well-written) but the subject matter strikes too close to today’s headlines. A couple examples come from Francis:

Page 277: Foreshadowing of DOGE?

One of the major recorders of the reign of George III, Horace Walpole, “was always ready with a diatribe, waxed on in scathing letters to various friends: The nation has leaped from outrageous war to a most humiliating supplication for peace…. Such accommodating facility had one defect—it came too late…. How one blushes to be an Englishman. To this he would add, ‘Children break their playthings to see the inside of them…. We have been like babies smashing an empire to see what it was made of.’

The king also pardoned a few hundred criminals on the condition they joined the army; … horse thieves, poachers, bigamists and at least one highwayman.” (page 462)

Page 308: Congressional foibles—way back when

“Congress resisted shoring up the nation’s revenue system with taxation. “Do you think, gentlemen, that I will consent to load my constituents with taxes when we can send to our printer and get a wagonload of money?” one delegate asked. The treasury consequently sent cash in great stacks to the army, along with shears to cut individual bills from the sheets of money…… on. “Do you think, gentlemen, that I will consent to load my constituents with taxes when we can send to our printer and get a wagonload of money?” one delegate asked. The treasury consequently sent cash in great stacks to the army, along with shears to cut individual bills from the sheets of money……”

In his visit to the Atlanta History Center, twice used expression “Not worth a Continental” This was a reference to the worthless paper that the Continental dollar had become. There was a lot of hyperinflation. Adding to the woes, the British printed counterfeit money which could be distinguished because it was printed on better paper with few misspellings. (As a kid I heard the expression that something “wasn’t worth a Continental damn” Hmm.

The other aspect of the book was that Atkinson’s grisly descriptions and of the disease and bloody battles–especially those at sea (most notably John Paul Jones capture to the British warship Serapis.) He said at his talk that he also wanted to show the brutality of war so readers would understand what those in combat went through.

This excerpt from page 584 of the book illustrates this:

“Illness was a way of life—and death—aboard ship in the age of sail. Of seventy thousand seamen in the Royal Navy this year, more than twenty-four thousand would sicken, a morbidity rate exceeding one third. During the Seven Years’ War, typhus and other diseases killed nearly half of the French mariners who sailed for Canada in 1757, and the survivors brought enough pathogens back to Brittany at the end of that year to also kill five thousand civilians. In the same bleak tradition, the ships that dropped anchor at Brest in mid-September bore eight thousand sick and dying French seamen, plus three thousand invalid Spaniards. So many corpses had been tossed overboard in English waters by the end of the voyage that residents of Cornwall and Devon supposedly would not eat fish for a month. The tally in Brest included 300 sick aboard both Palmier and Destin, 44 dead and 500 sick on Augustus, and, on Villede Paris, 61 dead and 560 sick. Of those still alive upon reaching shore, “a great many perished in no time,” a cadet from Picardy wrote. “I watched the covered wagons carrying the dead to their graves. They passed under my windows in a stream.”

We were both relieved when we finished the book. Not because weren’t impressed with Atkinson’s work, but this is — for the lack of a better word — heavy reading. Our nation was founded in division and bloody violence and given current event here in the first half of 2025 doesn’t make it any easier.

We finish with Francis’ Four Star Amazon Review

Apocalypse Then

Vincento Ibenez wrote The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, a best-selling novel based on the horrors of WWI in 1916. In like manner, Rick Atkinson’s: “The Fate of the Day” illustrates how Plague, War, Famine and Death were elements common in both European and American venues in the 18th through 20th century. While the first book in his trilogy reads quickly and captures the landmark events which shaped the onset of hostilities, this book shows the rocky aftermath of lofty ideals colliding with hereditary rule involving limited communication, inexperienced soldiers and commanders, mercenary troops, naval blockades, shipwrecks, indecision, poor planning and delays. These, coupled with unwieldy economies, led to supply shortages, exposure to heat, cold and illness and futile campaign seasons. Episodic savagery and mistreatment spared no one including Native Americans, enslaved persons, impressed seamen and prisoners of war. Moments of military and political heroism, cowardice, stupidity, cupidity and genius also occurred, which all helped push events towards their ultimate resolution. Although as well-written and researched as its predecessor, I found this book a more difficult read, perhaps because of the extent of human suffering it describes. Was it too long? Possibly, but effort and suffering were molten elements in this conflict which had to slowly harden for a new nation to form. Documenting the toll it exacted serves a purpose. The now legendary exploits of John Paul Jones comprise the most riveting portions of this book, and, given the military stalemate of those years, explain why he stands out even today. This is American History, written large, ideal for readers interested in the origins of our country and its anti-autocratic zeitgeist.

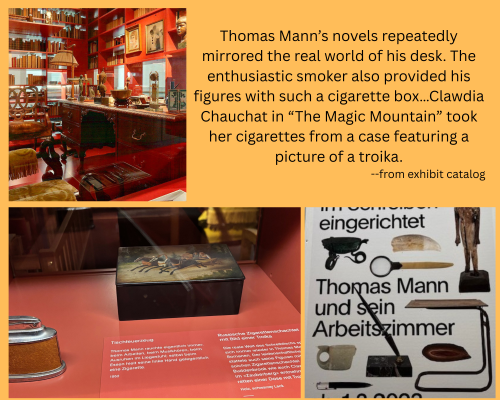

The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann

This is the 101st anniversary of publication of Thomas Mann’s classic novel. Not only did Mann win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1929, but he has special connection to GRSG. In the book Writers of the 70’s: Thomas Pynchon, Joseph W. Slater explains the link between Pynchon and Mann:

When Gravity’s Rainbow appeared, most critics dwelled on Pynchon’s similarity to Joyce. However, we should note that a more logical affinity would be with Thomas Mann, also a product of this period. In the irony of his narration, his mastery of the leitmotif, and his similarity of theme, Pynchon has much with common with Mann, who has many times been called a literary equivalent of Max Weber. It is perhaps no accident that the first appearance of the Angel in Gravity’s Rainbow takes place in the sky of Lübeck, Mann’s home.

Like Mann, Pynchon is interested in the polarities between the Northern and Southern cultures. In the fiction of both writers, North stands for rationality, discipline, civilization, alienation from nature; with South Are associated irrationality, freedom, nature, fertility.

Overview

Francis’ Amazon review provides an excellent overview of the book. Here’s Part 1 of “TB or not TB”

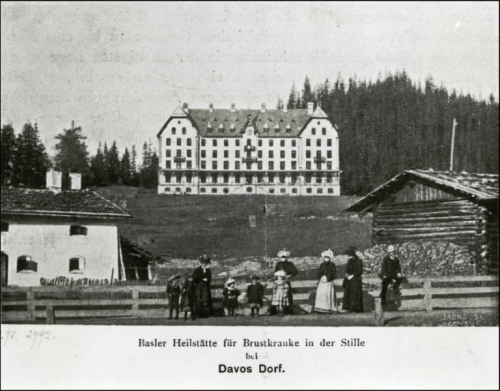

In 1912, Thomas Mann visited his wife, Katia, convalescing in the alps at a tuberculosis sanatorium in Davos Switzerland. It gave rise to the fictional Berghoff Sanatorium in “The Magic Mountain” long before Davos became a playground for barons of industry and heads of state attending The World Economic Forum. But even in that era, when people, not goods, were being consumed, and mycobacteria were the consumers, elite Europeans still formed cliques, intrigues and dalliances in the sanitariums that housed them as they recovered from an unpredictable illness.

The book introduces Hans Castorp as he visits Davos, sharing with readers his opinions on the behavior and conversations of its inhabitants. After his stay is unexpectedly extended, Hans, neither a hero or anti-hero, is seen as someone capable of enjoying comestibles, scenery, music and cigarettes and willing to learn from what he can gather from social encounters. As an amiable passenger on a ship of ambulatory consumptives, Hans provides Thomas Mann, the book’s author, a foil to sketch character, debate religion, philosophy and politics, discuss psychoanalysis, and explore romantic desire, suffering, death and time.”

The remainder of the review is at the end of this post.

Besides Pynchon

There were other reasons for selecting The Magic Mountain as Murray’s scheduled trip to Switzerland in June requires to read something voluminous and relevant to the places he was traveling. (For further explanation read “Swiss Reading Notes” from his Book Shopper blog.) Like Francis I had tried to read the book decades ago, remembering little except it was set in a sanitarium and it was supposed to be a metaphor for the world order in the turn of the 20th century.

We read the “new” (1995) translation from the German by John E. Woods. This translation of Mann’s works has made the book readable, and brought out of nuances of the language (including Mann’s description and humor) . This obit from The New York Times gives a full account of Woods as a translator and coincidently he was born in Indianapolis and his works are housed in the Lilly Library on the campus of Indiana University (our alma Mater).

Strengths

The Medicine

As you would expect, I defer to Francis on the medical aspects of the book. Francis wrote “Thomas Mann’s discussion of the biology of human tissues and the evolution of their cellular structure is remarkably well done and still quite accurate today.” He liked this passage about human skin.

“Your sculptural outline, if one can speak of it that way, is fat, too, of course, if not to the same extent as a woman’s. For our sort, fat normally is only a twentieth of total body weight; a sixteenth for women. Without our subcutaneous cell structure we’d all end up looking like some sort of wrinkly fungus…. Page 259 “Well, then—skin, you say? What should I tell you about your sensory envelope? It is your external brain, you see. Ontogenetically speaking, it has the same origin as the apparatus for the so-called higher sensory organs up there in your skull. You should know that the central nervous system is simply a slight modification of the external skin. Among lower animals there is no differentiation whatever between central and peripheral—they smell and taste with their skin. Just imagine it—the skin is their only sensory organ. Must be quite a cozy sensation, when one thinks about….

Since the medicine practiced at the sanitarium was led by Dr. Behrens his convictions on the treatments were a major influence. We learned about the pneumothorax treatments where the lung is intentionally collapsed, and the patients bond together with their “unpleasant whistle, harsh, intense…it reminds one of the music you get from one of those inflatable pigs you buy from the carnival (Mann humor p48).

“Pharmacology and toxicology are one and the same thing—we were healed by poisons, a substance considered an agent of life could, under certain circumstances, in a single convulsion kill within seconds.” ( p 568)

Philosophical and Political

At the beginning the Hans meets the Italian Settembrini an intellectual who values humanism and democracy. Later Mann introduces Naptha a Jesuit who has radical communist sympathies. The men frequently debate their respective positions. (for pages and pages) and Hans and his cousin Joachim frequently observe these often-fiery arguments.